Who Goes There?

Do I really need to introduce you to Stephen King? Nah, I don’t. So this is not so much a cursory look at King’s life and works as my own personal experience with him, because I have to admit, I was slow to read King at all. A lot of people have probably read him in high school, but I didn’t read a single word of his until I was in college; that’s not a gloat or anything, that’s just the reality of the situation. Had I read King earlier I probably would’ve been more entranced. My first exposure to King was “The Gunslinger,” the short story that later became part of the novel of the same name, the first in his Dark Tower series. I remember basically nothing about it. But later I read Different Seasons, his novella collection (although I will die on the hill of arguing Apt Pupil and The Body are full novels), which was sort of a mixed experience but mostly positive, although honestly The Shawshank Redemption improves on its source material in several ways.

Then last year I read ‘Salem’s Lot, his second novel, and I was sort of impressed; I love the first half and while the second half is oddly not nearly as scary (it loses its foreboding tone once the vampire-hunting gets underway), I liked that too. Good novel, even if it proved to be ground zero for so many of King’s… well, let’s call them quirks. King has written a lot. Like a fuckton. Like it’s intimidating to see just how many novels he’s written, although his list of short works is more manageable. Point being, King inevitably repeats himself; he has a list of go-to tropes and plot devices, and probably even turns of phrase that he can resort to over and over. I don’t really blame him: Philip K. Dick had a set of formulae too. But it’s also easy to poke fun at King’s tendency to, for example, set a given story in his home state of Maine—although today’s tale is an exception.

Despite being labeled a horror author, King has at least dabbled in pretty much every genre you can think of, including some good ol’ science fiction. “The Jaunt” is one of his more famous short stories (admittedly his short stories are not nearly as famous as his novels and novellas), and it’s the most pronounced example of him combining SF with horror in that both genres about equally play off each other here.

Placing Coordinates

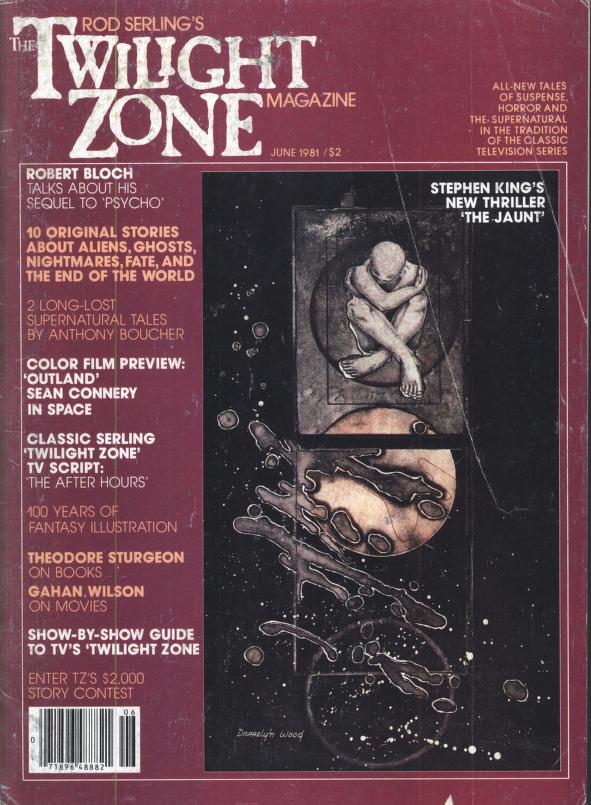

First published in the June 1981 issue of Twilight Zone Magazine, which is on the Archive. Because this is a King story from his prime era it’s very easy to find in print. The obvious choice is Skeleton Crew, which contains, among other things, The Mist. (I don’t know why I got The Mist as a standalone paperback, that was a waste of money. Actually several of King’s novellas have been resold as standalone paperbacks despite being only marginally cheaper than the collections they appear in.) The weird thing about “The Jaunt” is that it hasn’t been anthologized much; in four decades it’s been anthologized in English only a couple times.

Enhancing Image

Mark is taking his family for a business trip; in the old days they would’ve taken a ship to Mars, but with the Jaunt they can fall asleep and wake up at their destination in what feels like seconds. The Jaunt (with a capital J) is a revolutionary method of transportation that has made moving things and people between planets as easy as possible. Mark has Jaunted before but his wife Marilys and son Ricky and daughter Patty have not before. As they’re waiting to get a hit of sleeping gas (you have to be rendered unconscious before Jaunting), Mark passes the time and indulges his kids’ curiosity by telling them the story of how teleportation was invented; the kids would know little bits and pieces already, but Mark decides to tell them enough of the story, if not all the grisly details.

A few things to note before we get into that origin story…

King would’ve written “The Jaunt” circa 1980, or maybe earlier, and indeed this could not have been written any later than the early ’80s with how much it explicitly references OPEC and the oil crisis in the ’70s—a rather specific period in American history that the characters in this far-future setting treat like it was a recent and life-changing happening. I find this funny, because while the oil crisis no doubt impacted millions of Americans who were there to live through it, even people born, say, 1990 and later would have basically no context or sense of attachment with that period. The story shows its age by using what was then a recent time in history and overestimating how people in the future would relate to said time. Jaunting would be considered a monumental breakthrough in transportation regardless of when it was invented, but while King’s decision to date the story may seem superfluous, it does what most if not all science fiction sets out to do: not to predict the future but to comment on the present.

Also, if you’re a seasoned SF reader then you probably thought of jaunting (lower case l) as depicted in Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, which was by no means the first use of teleportation in SF but definitely had one of the most creative and influential uses. I figured, even before starting to read this one, that “The Jaunt” was harking to Bester’s novel, and that it would subvert our expectations about the mechanics of teleportation in some way since it’s clearly a horror story. Rather than let the reference go unspoken, though, King goes out of his way to let you know that he too manages to fit reading science fiction into his no doubt busy schedule. It’s one of those hat tips to fandom that makes me roll my eyes, but it also makes me wonder if “The Jaunt” would’ve gotten a Hugo nomination had it been published in an SF (and not horror) magazine.

Get this:

“Sometimes in college chemistry and physics they call it the Carew Process, but it’s really teleportation, and it was Carew himself—if you can believe the stories—who named it ‘the Jaunt.’ He was a science fiction reader, and there’s a story by a man named Alfred Bester, The Stars My Destination it’s called, and this fellow Bester made up the word ‘jaunte’ for teleportation in it. Except in his book, you could Jaunt just by thinking about it, and we can’t really do that.”

Anyway, about Victor Carew. The Carew story is when “The Jaunt” starts to grab my attention and as far as I’m concerned it’s the good SF-horror story that, like one of those Russian toys, is nestled inside a less scary and more cliched story. Carew was a scientist who struggled to retain autonomy while under government surveillance, using a barn as a makeshift laboratory and, like Jeff Goldblum’s character in The Fly, using this space to work on teleportation. The good news is that he finds that inanimate objects can be teleported from Portal A to Portal B with no issues; this alone would’ve revolutionized transportation, being able to move cargo between whole planets without a human driver. But of course this is sort of a cautionary tale and Carew does something that sounds reasonable but which will prove to have very mixed results: teleporting living things.

Having experimented on himself partly (he “loses” two fingers), Carew wonders if something can go through Portal A wholesale and come out of Portal B unscathed. Now, rather than experiment on people, Carew does the sane thing and tests Jaunting on animals—more specifically white mice. The mice (King erroneously calls them rats at one point) unfortunattely don’t fare well with teleportation: they come out the other end seemingly unharmed, but every one them dies soon after Jaunting. What’s more interesting is that if a mouse is put through Portal A tail-first and only partly subjected to the Jaunt, such that their head is still on the side of Portal A, they’re fine; if they’re put in head-first, however, with their head at Portal B and their tail at Portal A, they die even if they’re not completely teleported. Clearly then the mice dying has something to do with vision—what they’re seeing at that point between Portal A and B.

“What the hell is in there?” Carew wonders. Indeed.

I was wondering if King would go in a body horror or cosmic horror direction with this, and turns out it’s a bit of both. The body horror stems from how teleportation, if done gradually, reveals the insides of anything being teleported, such that we’re able to see the organs of the mice as they’re put slowly through the portal. The effect is uncanny and King, admirably, doesn’t dwell on it for too long, since he has another trick up his sleeve—that being the cosmic aspect. You see, teleportation takes a tiney fraction of a second, but during that incredibly brief time the subjective time it takes to Jaunt is enormous, although Carew does not realize this immediately. After all, the mice, aside from acting dazed when they come out the other end, don’t show any physical signs of being on the brink of death. What, then, could be killing them? Doesn’t matter, at least to the government, because Jaunting works and it’s about to change everything.

The results of the announcement of the Jaunt—of working teleportation—on October 19th, 1988, was a hammerstroke of worldwide excitement and economic upheaval. On the world money markets, the battered old American dollar suddenly skyrocketed through the roof. People who had bought gold at eight hundred and six dollars an ounce suddenly found that a pound of gold would bring something less than twelve hundred dollars. In the year between the announcement of the Jaunt and the first working Jaunt-Stations in New York and L.A., the stock market climbed a little over two hundred points. The price of oil dropped only seventy cents a barrel, but by 1994, with Jaunt-Stations crisscrossing the U.S. at the pressure-points of seventy major cities, OPEC solidarity had been cracked, and the price of oil began to tumble. By 1998, with Stations in most free world cities and goods routinely Jaunted between Toyko [sic] and Paris, Paris and London, London and New York, New York and Berlin, oil had dropped to fourteen dollars a barrel. By 2006, when people at last began to use the Jaunt on a regular basis, the stock market had leveled off seven hundred points above its 1987 levels and oil was selling for six dollars a barrel.

By 2006, oil had become what it had been in 1906: a toy.

Again I’m amused that King made the invention of teleportation so close to what would’ve then been the present day. What is he trying to say here? Genuine question, although I have to think it has to do with what was then (and still is, really) a mad search not only for alternative energy sources but to make those sources commercially viable. Sadly he doesn’t go deeper into the socio-economic implications of Jaunting (I imagine truckers would be mad about being out of a job), but he does enough that we’re given a juicy slice of how society in the future could be changed radically. And hell, even if you consider the negatives, the environmental consequences (there don’t seem to be any drawbacks in this regard) alone would make Jaunting a godsend not just for most people but for life on Earth generally.

A shame about those who Jaunt while still awake…

There Be Spoilers Here

Turns out Jaunting does have a physical effect on people, and there’s a reason why Carew is not able to see that by testing on the white mice. Apparently Jaunting while awake (although not when asleep, weird) turns your hair white (assuming it’s not already) while also aging you massively—physically, with the hair, but especially mentally. I’m embarrassed actually that it took until mere minutes prior to my writing this that the reason why Carew doesn’t see a physical change in the mice is that their coats are already white. In fairness the mice having their coats unchanged is a detail that’s unusually subtle by King’s standards, and it makes me think about how much better “The Jaunt” could’ve been had he put more of that storytelling discipline into action. I know I may sound unfairly harsh to the most popular horror author of all time, but King really does have moments where he’s able to push himself to the realm of true artistry, something higher than workmanlike technique; sometimes he really doesn’t, though.

(My favorite King short story is still “The Reach,” which is an unusually low-key outing for him, though that paid off with a World Fantasy Award win. It’s refined and effective as both a ghost story and simply as a work of fiction, and if you want prime King then I’d say that’s an example.)

So now we’re at the end. The time has come for Mark and his family to Jaunt to Mars; they get the gas and at first everything seems fine when they arrive at the other end. The only thing is that Ricky, being a dumbass, intentionally held his breath during the gassing and stayed conscious during the Jaunt, with predictably horrific results. Like with other people who supposedly stayed conscious during the Jaunt he comes out the other end with his hair snow-white, only this time, rather than being dazed like the mice, Ricky is laughing mad to the point of clawing his own eyes out while he cackles. Presumably Ricky will not live long, and to say this trip for the family proves traumatic would be an understatement.

A few questions:

- Since the Jaunt has been proved to be potentially deadly, and in a dramatic fashion at that, you’d think there’d be more safety measures. I get that if “The Cold Equations” can work in spite of how implausible its situation is then so can “The Jaunt,” but with the former I get the feeling (well actually we know this from correspondence between John W. Campbell and author Tom Godwin) that the decision to forego measures that would’ve saved the girl in that story was deliberate, whereas in “The Jaunt” it feels like a way for King to sneak in a scary ending.

- If all it takes for someone to stay awake during the Jaunt is so just hold their breath when being gassed, shouldn’t there be more cases like this? We’re given the impression that surely no one would be stupid enough to do that, given that Ricky is shown to be only a mildly stupid child, shouldn’t there be more cases of children dying from the Jaunt? I know that sounds morbid, but surely it’s no more morbid than quite a bit of what King’s written over the years.

- Come to think of it, how come the attendants didn’t notice that Ricky wasn’t inhailing the gas? Couldn’t they tell? Shouldn’t there be some kind of backup measure to make sure that someone is unconscious before Jaunting? You have a two-step authentication process to check your damn bank statements on your phone, there should probably be something extra here. Not that the story as a whole doesn’t work, but the ending specifically would not be allowed to happen if even rudimentary safety measures were in place.

- Children should probably not be allowed to Jaunt, right? It sounds like too much of a safety hazard. I know the obvious counter-argument would be that children are allowed in cars all the time and cars kill far more people in a year than sharks and airplane accidents combined (by like a lot), but there are also measures in place to try to minimize car fatalities. Granted, when “The Jaunt” was being written cars were far less safe than now and some people even today are reckless enough to cheat around using seatbelts. Still, the red tape for a Jaunting accident involving a child would be tremendous.

Anyway, even if I ignored the leap in logic, it’s too over the top for me to find scary. Ricky, a character whom we’ve gotten to know very little up to this point, does something monumentally stupid so that we can get a shocker ending. You could argue that it justifies the frame narrative, since otherwise the story just ends once Mark is done telling the story within the story, but I’d retort by saying that at least if the frame narrative is gonna be here at all then an ambiguous and moody ending would do better. We already had some body horror earlier that was creative and restrained enough that King left a good deal to the imagination. Personally I think we could’ve done without the frame narrative entirely; it’s not like Mark and his family are more compelling voices than Carew, and I was far more gripped by the substance of the story that’s being framed than how it was being framed.

A Step Farther Out

Kinda mixed on this one. There’s a pretty interesting SF-horror narrative nestled within a rather pointless frame narrative that not only verges on cornball but has a twist so obvious that it can be seen from orbit. It wouldn’t take too much to reframe the narrative in a documentary-like fashion, like Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Dunwich Horror,” wherein we’re like witnesses to a series of realistic but supernatural events. Unfortunately that requires a degree of restraint that King fails to practice here, and the result is ultimately too overblown for me to be genuinely spooked by. On the bright side, it’s memorable! King is aware that readers, even in 1981, are well aware of teleportation as a genre chestnut and tries admirably to subvert our expectations regarding this technology. That he’s able to conjure something menacing out of tech that, realistically, would change society for the better, is a sign of talent. It’s just a shame that the execution renders the story not all that scary, and also maybe too self-conscious.

See you next time.

One response to “Short Story Review: “The Jaunt” by Stephen King”

I did very much appreciate Steven King’s book on writing but have never been a fan of horror stories. What I do know is that if the bugs were ever worked out, the grim reality of humanity jaunting across the galaxy would be the real horror.

I do so enjoy your posts, Brian.

LikeLike