(Contains spoilers for “The Ash-Tree,” “A Warning to the Curious,” and “‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.’”)

Montague Rhodes James was born in 1862 and died in 1936, incidentally the same year as Rudyard Kipling; and with that, English literature lost two of its finest writers of the supernatural. It wasn’t the only thing they had in common: they were both conservatives of a breed that seemed to die out following the erosion of the British empire, both given to a distrust of women (Kipling more explicitly), both seeming to be relics of a prior age—a status which makes them a bit of a challenge for modern readers. More endearingly, both were consummate and compulsive storytellers. Kipling read stories to his children while James often wrote his stories with the intention of reading them aloud to his friends, which he would then do at Christmastime gatherings. They can’t help it; it’s like a second language for them. But whereas Kipling wrote almost every kind of story then conceivable (adventure, fantasy, science fiction, horror, you name it), James wrote only one kind of story: the ghost story. As he admits in “Stories I Have Tried to Write,” a brief but telling essay, “I never cared to try any other kind.” It’s a good thing he was perfect for such a niche job.

I’ve been reading some M. R. James as of late, or in a few cases rereading. I’ve said before that I’m a bit of a slow reader, and even then I struggle to retain information; but there’s also a pleasure in rereading something juicy, and James’s writing often demands closer examination. It’s occurred to me that James really was one of the best horror writers of his time, and he did this despite (by his own admission) being adept at only one specific kind of story. If you read five M. R. James stories in one day (which I wouldn’t recommend, because each requires at least some time to digest) then you will at some point feel like you’re reading five variations on the same story—the primordial M. R. James story which may not exist. “‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’” and “A Warning to the Curious” were written more than a decade apart, but read like the offspring of the same mother—or, to evoke the things lurking in the ash tree at the climax of that story, siblings in the same brood, belonging to the same monstrous spider-queen. To make a more film-nerd comparison, James’s fiction is sort of like the movies of Yasujirō Ozu, in that both artists seemed preoccupied with toying with the same set of ideas, creating works that are similar enough to each other, with subtle and at times profound differences.

In James’s case there is a tangible obsession with the distant past—in many cases the positively ancient past. This wasn’t just a hobby for the man, mind you. James was one of those writers who wrote relatively little fiction (his complete set of ghost stories has been printed in volumes under 500 pages) because he had a day job that both covered his ass financially and was respectable. He spent pretty much his whole adult life in academia, at a few different colleges, from undergrad all the way to senior positions. He was a professional medievalist, and he did not fuck around when it came to uncovering artifacts and works of architecture. If he were alive today he might be one of those “lost media” YouTubers, but ya know, more cultured. Something to keep in mind about James is that, being a Briton and living in the UK most of his life (he did like to travel), he had a first-hand conception of the ancient that filthy Americans like myself simply don’t have. For Americans the “ancient” past goes back to about the 1600s, but for someone who’s traveled through the UK and continental Europe this conception of the past goes back several more centuries. In this sense his story “The Ash-Tree” might be one of his most well-known, at least for American readers, because of its dealings with Puritans and the persecution of alleged witches—things Americans are likely to know about. Fans of Nathaniel Hawthorne will be sure to seek out this one especially.

But more often than not the terrors that haunt James’s protagonists are unspeakably old and ethereal, perhaps more monster than man. Not only are the living characters unable to communicate with these apparitions, but they’re barely even able to understand their existence in the physical world. You may be thinking there are only so many ways one can write about ghosts, or even imagine ghosts; but even comparing James to Kipling, or Montague Rhodes to Henry (that other great ghost story writer), shows that there’s more than one way to skin a cat. Indeed, unlike the popular conception of ghosts up to the Edwardian period, James’s (I’m talking about M. R. now) ghosts are decidedly meaner, crueler, more unreasonable, and more impenetrable. Or, to quote H. P. Lovecraft in “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” in which he articulates James’s virtues better than I could:

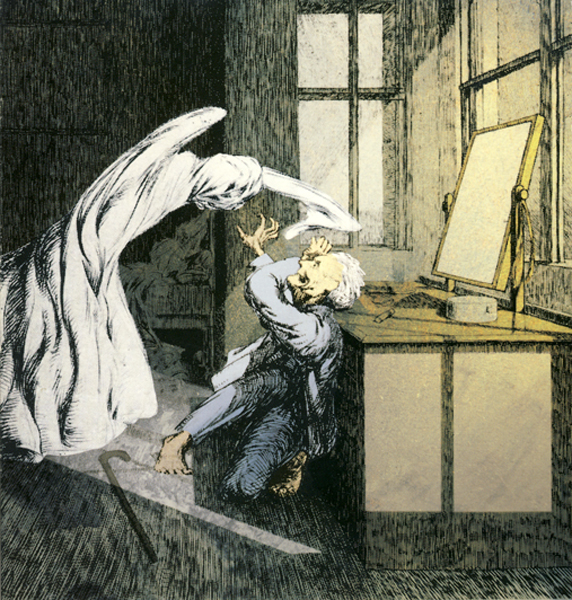

In inventing a new type of ghost, [James] has departed considerably from the conventional Gothic tradition; for where the older stock ghosts were pale and stately, and apprehended chiefly through the sense of sight, the average James ghost is lean, dwarfish, and hairy—a sluggish, hellish night-abomination midway betwixt beast and man—and usually touched before it is seen. Sometimes the spectre is of still more eccentric composition; a roll of flannel with spidery eyes, or an invisible entity which moulds itself in bedding and shews a face of crumpled linen.

That latter description, by the way, applies to the ghost at the center of what is arguably James’s masterpiece, “‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.’” This story, one of the finest ghost stories of all time, also happens to be a perfect encapsulation of James’s wants, fears, virtues, and limitations; it is a microcosm of everything relevant to and about M. R. James. We follow an academic, Professor Parkins, journeys to the coastal town of Burnstow (based on the real town of Felixstowe) for vacation, where he ends up golfing with a fellow at the same inn who mostly goes simply by “the Colonel.” Parkins gets word that there’s an attraction within walking distance of the inn that may be of interest to him: the site of a Templar preceptory, now mostly buried. The site would be at least 600 years old, and yet, England itself being such an old country, there might be something worth digging for. One day Parkins goes to the site as part of his beach walk, and digs out a whistle that, despite being caked in and clogged with dirt, remains miraculously intact. There’s writing on the whistle, in Latin, which Parkins can only partly make out, but which he translates as, “Who is this who is coming?” Having cleaned the whistle, and out of curiosity, he decides to use it. This is a mistake. The whistle’s owner has been dead for centuries, and yet upon Parkins’s discovering the whistle has been brought back into this world—first as a vague human-shaped specter that stalks Parkins on the beach and later taking possession of the aforementioned “crumpled linen.” This might be the only time in history the stereotypical bedsheet ghost is made threatening.

Everything is neatly laid out for us. We have an intellectual but sort of hapless protagonist, a pastoral locale that seems inviting but which houses an ancient evil (locations in James stories always seem either to be wide open spaces or storied buildings like cathedrals and old colleges, no in-between), a spirit of the distant past which is catapulted into the present by some cursed object, and ultimately an anti-intellectual message. For James, the past seems to always be just one bad move away from resurfacing, on a collision course with the present unbeknownst to the latter. The central character of “A Warning to the Curious” takes what is supposedly the last buried crown on England’s coasts, made to stave off foreign enemies, and draws the unwanted attention of something—and, even after returning the ancient crown to its rightful place, he pays for his transgression. Similarly the latest in a line of Puritan landowners falls prey to a witch’s curse that his ancestor had brought upon the family in “The Ash-Tree,” with the witch continuing to wreak vengeance long after her execution. According to James, the past is never dead—merely dormant. In cosmic horror a rule of thumb is to never alert the eldritch horror to your presence, but while James’s ghost stories are not cosmic, they do have a similar rule: do not wake that which is sleeping. All things considered, Parkins gets off lightly.

It’s funny to think that James would revolutionize the ghost story, since he was about as far removed from the revolutionary as is possible. He was a reactionary, a staunch anti-Modernist, a misogynist, and if contemporary accounts are to be believed, a bit of a man-child. He had no sense of worker solidarity, wasn’t remotely interested in making the world a better place, and seemed to be a walking goldmine of useless trivia (again, think “lost media” YouTuber); and yet it could be argued that this sheltered lifestyle, this state of being perpetually knee-deep in the past, had nurtured James’s writing rather than hindered it. Sure, you (possibly left-leaning reader—or maybe not) and I find the politics of, say, H. G. Wells, a lot more agreeable, but I don’t think Wells (at least young Wells) could’ve written such a menacing work of horror as “‘Oh, Whistle’” or “Count Magnus” or “Casting the Runes.” I’ve been having this thought, or rather question, tumbling around in my head lately: Is horror a conservative genre? Very loaded question, probably worthy of its own editorial at a later date. Historically some of the great horror writers were conservative, and certainly the best writers of ghost stories in particular have tended to be right-wing. It could be because conservatives go through life already being stalked by phantoms—by the specters of queerness, feminism, socialism, and what have you. M. R. James is a rare case where his artistry was often fabulous because of his backwards politics, and more specifically because of his crippling fear of the present.

3 responses to “The Observatory: For M. R. James, the Past Is Never Dead”

Seems to have take the academia part of his profession a bit more seriously than Tolkein. I feel for these medievalists who seemed to have the most passion for other writing projects! hah.

Thank you for the editorial. I always enjoy reading about authors I haven’t heard of.

LikeLike

It seems to me like James’s long time in academia made him narrow-minded (the stereotype that professors are left-wing is bullshit, a few of my professors were open reactionaries), but it also gave him the financial security to only do what he wanted. He wrote primarily for himself, without concerns for selling book copies, and what writer doesn’t dream of that?

LikeLike

We are also talking about a far different era than the present. But yeah, I had plenty of conservative professors — pretty common in history and philosophy.

LikeLike