Who Goes There?

Author, anthologist, and (curiously) radio personality, Ellen Kushner has been active off and on since the early ’80s. As far as I can tell she’s one of those writers who basically works within the confines of a single genre—in this case fantasy. Her 1990 novel Thomas the Rhymer won the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. Her Riverside universe is comprised of three novels plus a smattering of short fiction, of which today’s story is an example. “The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death” is a borderline sword-and-sorcery narrative and is, as Kristine Kathryn Rusch puts it in the introduction, “a coming of age story—with a twist.” Of course I won’t say what the twist is here, but this is one of those stories that’s arguably more pleasurable to think about with the gift of hindsight than it is to read in the moment. This is not necessarily a bad thing. It struck me enough that I’m now curious about picking up a couple of Kushner’s novels.

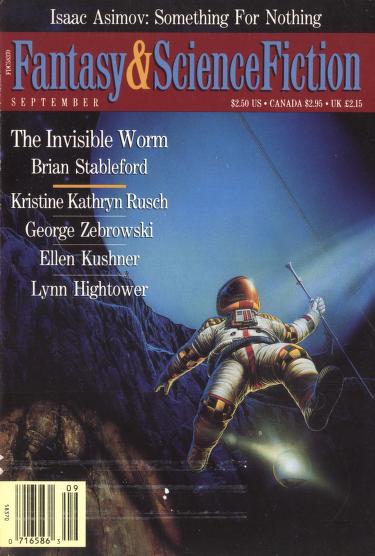

Placing Coordinates

First published in the September 1991 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It was then reprinted digitally in Strange Horizons, although you’d have to use the Wayback Machine to find that now. More conveniently it was reprinted digitally in Fantasy Magazine, which you can find here. Sadly Fantasy Magazine closed its doors late last year, so there will probably come a point when the site will shut down and you’ll have to use the Wayback Machine as well. For print appearances we have The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror: Fifth Annual Collection (ed. Ellen Datlow and Terry Windling), In Lands That Never Were: Tales of Swords and Sorcery from The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (ed. Gordon Van Gelder), and more recent editions of Swordspoint that include a few short stories set in the Riverside universe.

Enhancing Image

This story begins and ends with a wound. Richard St. Vier, master swordsman, has just taught some punk a lesson. This is a coming-of-age story, but not for Richard, who is already a fully-formed person and who for all I know could be the hero of another story set in the Riverside universe. Speaking of which, Riverside itself is sort of a red light district, “beyond reach of the law,” where Richard lives with his scholar friend Alec. The two make an odd couple, a brains-and-brawn pair that would probably strike people as funny in more civilized corners of the city, hence their residing in Riverside. “It would not have been a safe place for a man like Alec, who barely knew one end of a knife from another; but the swordsman St. Vier had made it clear what would happen to anyone who touched his friend.” It’s sort of unclear how platonic the two are, given some exchanges much later on, which would fit in with Kushner’s playing with sex and gender. Maybe they’re just roommates. Anyway, after the opening fight Richard is chilling when he’s confronted with a boy who’s probably barely in his teens, and whom he at first mistakes for a girl. The boy wants to work for the master swordsman as a servant, but Richard’s not interested. It’s clear the boy wants to become an apprentice, but Richard’s not biting.

In under 5,000 words we’re given a vivid picture of Riverside as a semi-historic low-fantasy setting, where magic doesn’t seem to play a part in the average person’s life, but at the same time this is certainly not the Renaissance of our world. It’s hostile and at the same time cozy, in a weird way. It could be because the stakes of this particular story are low. It’s essentially a slice-of-life narrative that will—without the reader realizing it—turn into something else, albeit without ever turning into an adventure. This is about relationships, about how characters perceive each other, and how the reader perceives these characters. There’s a bit of foreshadowing that I didn’t even catch the first time around with regards to the true identity of one of these characters. Despite being “friends” officially, jokey remarks between Richard and Alec imply maybe a friends-with-benefits relationships. (These two are so gay together it’s insane.) In short, it’s about deception, or at least lying by way of omission. Kushner is playing some tricks on the reader, but in a friendly, unpretentious way, which at first doesn’t seem serious but which provides some real food for thought. It helps that Kushner’s style is so breezy and so affable, such that it doesn’t surprise me this story would be reprinted online twice. When it appeared in the November 2011 issue of Fantasy Magazine it would’ve been two decades old, but it fits in neatly with short fantasy being published for the first time in the 2010s.

On returning home by himself, “in a cul-de-sac off the main street; part of an old townhouse, a discarded veteran of grander days,” Richard finds the lights are out on the first floor—but there’s someone inside. Not one to take chances, Richard takes out his sword and is about to enter slowly, only for a “small woman” to throw herself on him in desperation, pleading for protection. This is all pretty strange, Richard thinks, but out of sheer politeness he lets the girl into his apartment, albeit with caution. Eventually Alec comes home and assumes Richard really did get a servant, in a misunderstanding, but is pretty chill with the girl sharing the apartment for the night. (And oh my goodness, Richard and Alec are sleeping in the same bed, this is too much.) The next morning, however, and things are not what they had seemed before, for the girl turned out to be the teen boy mentioned earlier in disguise. I have to quote this exchange here since it a) it’s funny, and b) it neatly sums up the story’s gender-bending antics:

St. Vier eased himself onto his elbows. “Which are you, an heiress disguised as a snotty brat, or a brat disguised as an heiress?”

“Or,” Alec couldn’t resist adding, “a boy disguised as a girl disguised as a boy?”

It’s been a few days since I read “The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death,” partly because I had to let it simmer and also because I was feeling some mild burnout with writing, but since then I’ve come to appreciate how tightly knit this one is. For a story now over thirty years old it still feels “modern,” between the queerness, Kushner’s very readable style, and what turns out to be a striking thesis hidden in plain sight. (By the way, I suspect the queerness still holds up perfectly because Kushner herself is a queer writer, being bisexual.) Speaking of the thesis, you may be wondering, “If the damsel being a boy in disguise is the twist, then what would count as spoilers?” You see, that’s not the real twist…

There Be spoilers Here

Kushner bamboozled us, but goddamn it, she bamboozles us yet again! Alec’s joke earlier is almost correct, except it turns out the genders are reversed: it’s a girl disguised as a boy disguised as a girl. Now isn’t this confusing? The girl-as-boy, who trains with Richard and proves to not be a hopeless case but gets wounded in the process, has her true identity revealed. (You could theorize the girl is actually a trans boy, or at least an egg, but it’d only be a vague implication, and anyway there’s already enough going on that we probably don’t need further complications. At the same time this story was basically tailor-made for genderqueer readings.) Alec pulls a book with a blood stain on it out of the girl’s breast pocket, titled The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death (in a bit of a meta move), an erotic chivalric romance that, coincidentally, Alec’s sister also had. “It’s about some Noble girl who comes home from a ball and finds a swordsman waiting in her room for her. He doesn’t kill her; he fucks her instead. She loves it. The End.” In this case the swordsman doesn’t kill the girl, but he doesn’t fuck her either; yet there’s undoubtedly a symbolic deflowering as the girl gets her first taste of swordplay and bleeds for it. The metaphor is pretty blunt, but so effective that it made me reevaluate the story up to this point. Rusch wasn’t lying—it is indeed a coming-of-age narrative, a gender-bending symbolic taking of a girl’s virginity that’s at once traumatic and liberating. This is the kind of juicy material that made me buy two of Kushner’s books.

A Step Farther Out

At first I was wondering what Kushner was up to with this one, since at first it seemed like a pretty standard low-ish fantasy yarn with a stoic tough-guy swordsman at the center—only to find out the tough guy is not the point. Kushner plays with gender and symbolism in a way that is somehow both blunt (it’s pretty hard to miss) and yet timeless. It starts as one thing but then becomes a protracted metaphor for a young woman’s first sexual experience. An unexpected turn of events, but this is one of those surprises that caught me in its trap in the best of ways.

See you next time.

One response to “Short Story Review: “The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death” by Ellen Kushner”

Kushner’s “Swordspoint” is one of my favourite books, as is “The Privilege of the Sword”. I cannot recommend “The Fall of Kings”. It was coauthored and I did not find a single likable character in it.

LikeLike