Who Goes There?

Vernor Vinge died last month, in what turned out to be a battle with Parkinson’s; and it was one of the most crushing losses for the field in a long time, because Vinge was one of the most creative mind of his generation. Despite not being a very prolific writer, and despite his work being all over the place in terms of quality, Vinge at his best was one of those rare talents, like Philip K. Dick and Harlan Ellison at their best, who genuinely pushed the field in new directions and made readers and fellow writers see new horizons. His novella “True Names” is a seminal work of cyberpunk that came out just before the word “cyberpunk” would be coined, and modern readers will find it holds up to an eerie degree today. His duology The Peace War and Marooned in Realtime might’ve been the first prolonged attempts at speculating on human life right before and after the technological singularity—a term Vinge did not invent, although he did popularize it. His loosely linked novels A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky both won him Hugos, and more importantly they revolutionized the space opera during what was already a renaissance for the subgenre. Vinge is unwittingly responsible for a generation of Elon Musk fanboys—but let’s not hold that against him.

With the notable exception of “True Names,” Vinge is not known for his short fiction, although that didn’t stop him from winning the Hugo for Best Novella twice. “Original Sin” is pretty obscure, even as far as Vinge’s short fiction goes; so far I’ve seen a total of one solitary person talk about it, albeit positively. It’s early Vinge, and while it was published during Ben Bova’s tenure at Analog it might be a story John W. Campbell had bought right before his death; it reads like a classic Campbellian narrative—with a little twist. It’s flawed, in the way Vinge’s earlier writing tends to be flawed, but while it starts out rough it does have some points of interest.

Placing Coordinates

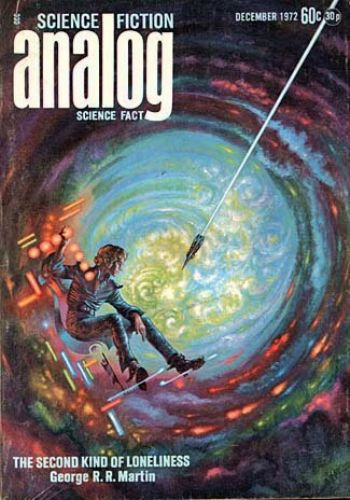

First published in the December 1972 issue of Analog, which is not on the Internet Archive but which can be found on Luminist. I happen to have a physical copy of this issue. “Original Sin” was then reprinted in the Vinge collections Threats… and Other Promises and The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge. Would be nice if we got an updated version of the latter since it doesn’t include the several short stories and novellas Vinge put out afterward.

Enhancing Image

Humanity has not only reached beyond our solar system but encountered intelligent life in the process. It’s been about two centuries since humanity made contact with the Shimans, a sentient bipedal race that’s like a cross between a kangaroo and a shark. The Shimans are a vicious bunch, but also fiercely intelligent—such that within two centuries they went from being pre-agrarian barbarians to having tech and societal structure on par with late-20th century America. Really the only thing keeping the Shimans from progressing even faster is a very short lifespan. “The creatures were really desperate: no Shiman had ever lived longer than twenty-five Earth months.” Enter Professor Kekkonen, a very old (although he doesn’t look it) biologist and both friend and employee of Samuelson Enterprises. Evidently humans have invented a rejuvenating technology that gives people something close to immortality (assuming they don’t get killed), and the Shimans want that same tech. Problem is, “the Empire” (Earth has apparently become united—and imperialistic) doesn’t want Shimans to have said tech; so Kekkonen has been conducting his work on Shiman biology very much illegally, with the help of a bribed “Earthpol” agent. Shit hits the fan, though, when Earthpol gets a whiff of Kekkonen’s scent, with a massive pyramid-like ship hovering over the planet.

Vinge structured the story such that mostly we follow Kekkonen’s first-person narration, which itself I think is a mistake since we can infer right away that the professor gets out of this ordeal alive, and this is supposed to be basically an action narrative. I’m also not big on the voice Vinge gives Kekkonen: it’s too snarky for my taste. This first-person narration is broken up a few times with a third-person perspective that’s all in italics and which is written in a very different style, evoking an old-timey fable or, more accurately, the Bible. The problem here is that Vinge is not a poet; his style at its best can be considered decidedly utilitarian. With the major exception of another early story, “Long Shot,” which is closer to a narrative prose poem than a short story (I think it’s fairly effective as that), Vinge doesn’t capture the imagination with his language so much as his straightforward way of describing things which are in and of themselves mind-bending. We remember the Bobbles, the Tines, the virtual world in “True Names,” and so on, but because of the things themselves and not because of Vinge’s language. The Bible-esque passages regarding the life-death cycle of the Shimans was an earnest attempt, but it doesn’t work for me and this story would’ve been a few pages shorter if I had gotten my grubby hands on it.

I’ve mostly gotten the negatives out of the way, so let me juxtapose that with something I think “Original Sin” does really well, which is the aliens. Despite having two legs, aping human technology, and even being able to replicate human speech (one wonders how they do that given their rows of shark teeth), the Shimans are decidedly not human. The third and final main character, after Kekkonen and Tsumo (the bribed Earthcop), is Sirbat, a Shiman escort is comes out of this story the most interesting of the three in no small part because of his aloof nature. He speaks perfect English and is perfectly willing to cooperate with the humans, considering what’s in for his race, but one also gets the impression he’s constantly holding back a part of himself—probably an urge to eat his own comrades. One reason Earth is very worried at the prospect of Shimans gaining nigh-immortality is that the Shimans are vicious, yes, but they’re also voracious eaters; indeed cannibalism is part of their very biology, since baby Shimans escape the “womb” by devouring their own parent. I say “parent” and not “mother” because the Shimans are single-sex, reproduce asexually, and they seem to all be male, although Vinge is unclear if the Shimans actually identify as male or if male pronouns are simply what the humans use for the sake of convenience. So let’s say the Shimans are males that happen to give birth.

“Original Sin” is basically a problem story, or rather a question story: Is it ethically sound to give an alien civilization technology that could make said aliens an existential threat to other intelligent life in the universe? Is it right for humanity to keep a powerful technology to itself for fear that there may be competition—possibly even a rival for the position of supreme intelligent race? Vinge has always had a keen moral sense, or at least a strong moral curiosity, which you have to admit makes his endorsing of anarcho-capitalism fucking bewildering. (In fairness he seemed to think other forms of anarchism are valid, but felt that anarcho-capitalism, for some reason, was the “correct” option. I’m sorry, I’m getting distracted.) So Kekkonen is in a tough spot: he was hired by a longtime friend to do a job that may or may not result in humanity’s eventual destruction, and at the same time the cop that Samuelson had bribed in the first place is practically begging him to not go through with the experiment. The Shimans of course wanna live a hundred years instead of just two, and wouldn’t Kekkonen feel like an asshole for denying a whole race a longer lifespan? It’s a curious dilemma that acts as good brain food—even if it becomes clear by the end which side Vinge supports.

There Be Spoilers Here

Using this section to talk about Tsumo, who’s a bit of a mixed bag as a character. Vinge ain’t half bad at writing women usually, but he’s on shaky ground with this one. Her backstory is interesting: she had a husband who served as a Christian missionary on Shima, and nobody knows what happened to him—possibly killed and eaten by his own followers. (Should probably also mention Christianity has taken off among the Shimans, despite and possibly because of their ravenous nature.) So Tusmo has a certain vendetta against the Shimans, although she denies this has anything to do with not wanting the little bastards to have extremely long lifespans. At one point towards the end she even seduces Kekkonen and sleeps with him in an effort to stop him from finishing the experiment. Not sure if this was necessary on Vinge’s part. Anyway, it doesn’t work, because Kekkonen reveals that Samuelson wants the Shimans to become competitors with humanity. This all feels like almost an inversion of the Adam-and-Eve myth, hence the title. Adam and Eve give up their immortality for the sake of knowledge, whereas the Shimans are already knowledge-hungry (on top of just being hungry in general) but seek virtual immortality so as to remove the cap for that knowledge-seeking. The “original sin” of the title also refers to the Shimans’ biologically mandated genocide and patricide—the fact that they must eat their own parents and then most of each other.

A Step Farther Out

Do I recommend this story? Hmmm, not unless you’re already familiar with Vinge’s writing and you’re curious about his early work. I would not recommend it as one’s first Vinge story because it’s more apparently flawed than his more mature work, and unlike his first story, “Apartness” (review here), it’s more confused. I actually considered giving up and picking a different Vinge story early on, because this story really does not start on the right foot; but I’m glad I kept with it, because it did get better as it progressed. I could’ve picked a worse story to review in paying tribute to someone I think of as one of the true masters of the field.

See you next time.