Who Goes There?

This introductory section is gonna be a bit long, bear with me. If you’re one of the three people who follows my Things Beyond posts then you would’ve figured I was to review the first installment of John Brunner’s novel The Stone That Never Came Down today, and you’ll also notice that this is very much not that review. Plans change. I did try reading that novel, but truth be told I bounced off of it so hard before getting even halfway through the installment, not to mention I was running out of time (my schedule has been merciless as of late), that I decided to just drop the damn thing. I found the stuff I had read to be both irritating and nonsensical, not helped by the fact that I had just come off of rereading Stand on Zanzibar. For a bit I thought maybe I was just Brunner’d out for the moment, but I think it’s more that going from good Brunner to bad Brunner caused whiplash; so then I was left with a hole in my review schedule that needed filling.

I also considered covering short stories by a different author, but I wanted to be fair to Brunner, so instead I figured that instead of forcing myself to cover a lesser Brunner novel we would get two Brunner short stories that will hopefully show him in a better light; helps that I’ve also been meaning to read some of his short fiction. As such I issued an executive order and today we’ll be talking about a very early but very interesting Brunner story with “Fair,” while the second installment of The Stone That Never Came Down will be replaced with another Brunner short story that’s been on my radar, “The Totally Rich.” As someone who, in recent years, has taken more to short stories and novellas than novels, I consider this move a net positive! Other than that everything else should proceed as normal; just ignore what I’m gonna be saying in July’s Things Beyond post.

The question remains, though: Who is John Galt Brunner? Depending on who you ask he’s one of the largely unsung geniuses of old-timey SF, and at the same time one of the largest providers of third-rate crap. He wrote a lot of novels that are now forgotten and/or loathed, but he also wrote a handful of novels that are said to be some of the best of their era, the most famous of these being the Hugo-winning Stand on Zanzibar. Brunner started writing as a teenager and would not stop until his death, but his career trajectory was a bit tragic; he did not get along with fellow British writers, being more accustomed to the American SF market and even being confused for an American at times. (I recently talked with an actual SF scholar, and it was not until the middle of our discussion that they realized Brunner was an Englishman.) Brunner was all of 21 when “Fair” was published—the scary part being that he was already five years into his writing career, his first work being published when he was 16.

Placing Coordinates

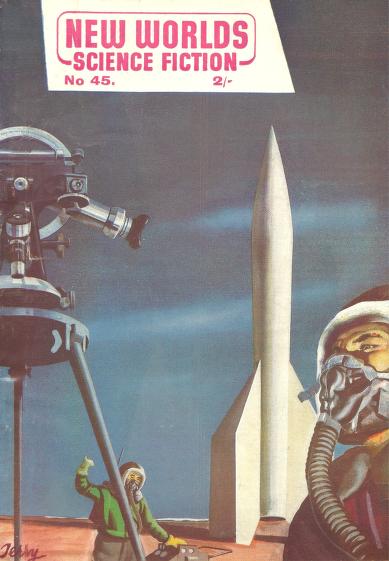

First published in the March 1956 issue of New Worlds, which is on the Archive. You may notice it was initially published under the pseudonym Keith Woodcott, but this was a very poorly kept secret. “Fair” has only been collected three times in English, and has not seen print since the ’80s. It was first collected in the Brunner collection No Future in It, then much later in the Ballantine collection The Best of John Brunner. I personally don’t consider The Best of John Brunner to be part of the Ballantine “Best of…” author series from the ’70s, given it was published much later and does not follow the design pattern of that series; this is one way of saying the cover for it is so bad that I consider it to be non-canon.

Enhancing Image

We start sort of in media res, and Brunner crammed a lot into these dozen pages. We follow Alec Jevons, “ex-test pilot, ex-serviceman, ex-child and ex-husband, ex-this and that, ex-practically everything.” Jevons is deep in middle age, probably in his fifties, and he’s certainly too old to be going to the Fair, a massive playground of the future; but he’s not here for the entertainment. Truth be told, it’s not clear why he’s here, even to himself. He came here knowing that not only is this a Fair but the first Fair constructed—even now the biggest and best of its kind. I would go into great detail as to what the Fair is like, but I’ll say that if you’ve played Final Fantasy VII and remember the Gold Saucer, it’s like that: a highly advanced pleasure park that hosts a variety of attractions, ideally for young people to get lost in, hence the Gold Saucer’s reputation as a time sink in that game.

There’s this cloud of fear hanging over Jevons as he enters the Fair, even though he must know he’s not in any immediate danger; rather the fear comes from the prospect of being outed as an old geezer and picked on by the youths. Context: this is obviously set in the future but not too far in the future, as the Cold War is still going on and there’s a strong whiff of post-war British slang among the nameless youths. Brunner, at this point, was far closer in age to the youngsters than to Jevons, and for most of the story you wouldn’t guess this was the case from how those youngsters are framed as devious and unknowable—and doomed. There doesn’t seem to be a war going on, but there’s the sense that there was a war not too long ago and, more importantly, that war could come again any day now. “A million people a night in this fair alone,” we’re told, a million people a night hiding “from the uncomfortable reality of silence and thought, from the danger of tomorrow, from the waiting death poised above them in the sky…”

Something to keep in mind is that Brunner came from a generation of Britons who were too young to see combat in World War II but old enough to remember Nazi bombers over British skies. While the future of “Fair” is too distant to be set shortly after World War II specifically, it still evokes a post-war England which saw a rise in juvenile deliquency and the shadow of a generation of dead and traumatized British men. When the Cold War began in the years immediately following World War II, you’d have children and teens who grew up in an environment where the possibility of sudden nuclear devastation was very real and very known. Jevons himself served his country but was dismissed due to his Russian heritage, something that he was apparently bullied for in his own youth. While Jevons fears the youngsters at the Fair he also pities them, with the insecure boys and their girlfriends, “tarts before they were twenty, but lost and empty and without a future since they were ten.” At one point Jevons gets hit on by a girl who is probably a third his age and it (rightly) unnerves him.

Let’s talk about style for a moment, because frankly it’s not something I dwell on in these reviews and I think this is a good example of style contributing positively to the substance of the writing. Brunner could’ve easily deployed a “function only” style that got the job done but didn’t stray far from beige, but he must’ve been listening to some records at the time becaue there’s a punchiness and a musicality with how he interweaves the third-person narration with Jevons’s internal monologue, such that it’s not always clear who is saying what. The result is that there’s a bit of confusion, yes, but also a sense of intimacy with how thought and action bleed into each other. Check out this early passage, wherein Jevons ponders his age and his generation’s role in the creation of the Fairs; see how we get two channels, first- and third-person voices, sharing the same space:

The Fair had been less elaborate in his young days. Watch it, Jevons! You’re starting to admit your age. (And why not? Because if you remember that you’ve been around that long, you admit that you were responsible—this was your doing, this mechanical time-destroying hurly-burly, this feverish seeking after temporary nirvana. This was your fault!).

Like I said, Brunner’s writing here is busy, even high-octane, but this was clearly a deliberate choice on his part.

It’s hard to figure out what Brunner likes, but it’s pretty easy to figure out what he doesn’t like. For instance, he clearly despises anything that serves to numb human consciousness, and he also hates the silly business that is capitalism; not to say that Brunner was what we would call a progressive figure, given his standoffish relationship with women, but at least he tried. When I went into this I expected the Fair to be a nightmarish setting, and for most of the story my expectations were supported. The escalator system that gets more intense as you venture closer to the center of the Fair evokes a highway system from hell, and the security guards, dressed like court jesters and called “Uncles,” are not the kind you’d wanna run into if you’re scared of clowns. Yet Brunner does something in the climax that, while I don’t think it was perfectly executed, made me second-guess the story’s intentions. There’s not a lot to spoil since this is a story heavy on mood (with jazzy parenthetical asides that would not look out of place in a much later Brunner tale) and world-building rather than plot, but let’s get to it.

There Be Spoilers Here

The twist is video games. Well, it’s not just that.

Given this was written in 1955, Brunner would’ve had no conception of video games; the phrase would not’ve been part of his vocabulary. Even so, the climax of the story, in which Jevons partakes in several “totsensid” sessions, perfectly reads a highly advanced virtual reality program. “Total sensory identification was what they called it.” Total sensory identification. Identification with what or with whom? With people who are not what you’d call the average Briton, it turns out. First a pilot, which aligns with Jevons’s own experiences enough, but then he becomes one half of a newly married African couple, then later—and this really hits him—one half of a Russian couple. There’s some wish-fulfillment at play, as a sort of necessary evil, but you have these white British youths being thrown into the shoes of non-British non-white people, as a sort of empathy exercise.

The Fair is not just there to entertain, or even to push people’s senses to their limits—it’s there also to try to save the current generation of young people. A switch gets flipped in Jevons’s mind and he has the epiphany that these people are being subliminally trained, in what we would now call VR, to empathize with humans from other countries and cultures. I know people meme about Brunner for his capacity to “predict the future” (a stupid sentiment, to be sure), but I’m still taken aback that in 1955 (when he would’ve written “Fair”) he envisioned the potential of video games as a force for good in people’s lives. The thing is, games (video and otherwise) are always to some degree interactive, which is what makes them different from other mediums. We’re not given much insight into how interactive the totsensid is, but from what we’re told it’s like having your consciousness transferred to another body. Even the purposely unpleasant simulations, like being a Malay diver who’s dying of illness, have their value in how they bend one’s consciousness. “It was not pleasant, but it was real.” It’s enough to convince Jevons to start working at the Fair himself, in what has to be one of the few happy endings for a Brunner story.

I can’t say I’m entirely convinced of the ending’s sincerity, but it did take the story in a direction I very much did not expect. Brunner goes to such lengths to frame the Fair as a hellish place, only to subvert this at the end, that maybe it would’ve come as too much of a shock no matter how delivered. What’s important is that it gave me something to think about. I also feel like I shouldn’t have to say this, but Brunner not only anticipated cyberpunk by a quarter-century but also subverted one of the pet tropes of that subgenre, namely the notion that intimacy with technology via virtual reality or cybernetics would dehumanize people. Samuel R. Delany posited something not too dissimilar in his novel Nova, wherein most people are able to plug in directly to machinery via implants, with the result being that these people are actually more content with their labor than us due to being physically connected with their work. Technology, created with compassion in mind, could save the world. That Brunner put thought into this when he would’ve been barely out of his teens is impressive.

A Step Farther Out

Brunner surprised me with this one, even having heard good things about it in advance. I would’ve expected something more amateurish, given his age, but he already had a good amount of experience under his belt and there’s a spry youthfulness to the style that almost feels like it could fit in with New Wave writings of a decade later. “Fair” is, however, distinctly a Cold War-era story, written at a time when both sides were doing hydrogen bomb tests and when Germany and Berlin had been recently divided. I don’t think this story would’ve made quite as much sense had it indeed been published a decade later, and I’m also not sure if an older (and presumably more jaded) Brunner would’ve believed enough in the happy ending to go with it. “Fair” is a near-masterpiece in miniature that sees one of SF’s mavericks at a very early stage, just experienced enough to know about sentence construction and young enough to throw caution to the wind. This may be setting too high a bar, but it does give me hope for future Brunner readings.

See you next time.

5 responses to “Short Story Review: “Fair” by John Brunner”

I really recommend the Jad Smith monograph John Brunner (2012). It’s a slim book that won’t take you too long to knock out (and it’s about a fascinating figure). It details how Brunner was never really accepted by either camp — Americans or Brits. It details the financial side of publishing at the time that I was simply ignorant of… and thus explains a lot of Brunner’s choices and constraints. His best novels simply took too long to write and were rarely financially successful so he was forced to publish or rework other novels.

Your connection to video games is a good one. I’m not sure why I didn’t register them as “video games” especially in the context of a Fair, that would be filled with games. “Nobody Axed You” (1965) is another early-ish Brunner worth tracking down. It served as one of many media-themed stories that inspired my series.

LikeLike

And “Lungfish” (1957) — a spectacular generation ship short story and probably my favorite early Brunner.

LikeLike

I need to read The Sheep Look Up. And maybe Quicksand. Seems like Brunner had ambitions that went well beyond the confines of the genre at the time but he also tried writing full-time, with mixed results.

LikeLike

Yup, I recently purchased Quicksand after I read the Smith book — his valiant attempt at a more mainstream novel that unfortunately was overshadowed due a delayed publication date that ended up being too close to when Stand was released (which also made little money despite critical success).

LikeLike

[…] Fiction (SFF Remembrance): Today we’ll be talking about a very early but very interesting Brunner story with “Fair,” […]

LikeLike