Who Goes There?

This is another case where I have to try to not fanboy out, becaue I respect Richard Matheson a lot and I’ll give anything he writes at least one try. Matheson entered the field in 1950 with a remarkable short-short story titled “Born of Man and Woman,” which instantly made him popular with readers and which remains (impressively for a debut) one of the more reprinted stories in all of genre fiction. Matheson’s subsequent efforts, including “Third from the Sun,” “Dress of White Silk,” “Witch War,” “Through Channels,” and others, were not quite to the level of that first story, but they showed a naturally gifted storyteller who casually wandered across different genres, from science fiction to straight horror. When Matheson turned to novels he proved good at that too, with I Am Legend and The Shrinking Man being two of the most disturbing and thought-provoking SF novels of the ’50s. He would win a Hugo for adapting The Shrinking Man into the 1957 film The Incredible Shrinking Man (the added word is justified, the film is indeed incredible), and Matheson’s new career as a screenwriter was just getting started.

There’s a high chance that if you tracked SFF film and TV in the ’60s that you encountered Matheson in screenwriting mode, including but not limited to the Star Trek episode “The Enemy Within” (really one of the better season 1 episodes) and some Roger Corman productions, including House of Usher and The Masque of the Red Death. The thing Mathesone would associate with the most, though, was The Twilight Zone—the ’60s and ’80s runs but especially the former. Along with Charles Beamont, Matheson contributed quite a few scripts to the original series, second in quantity (although not necessarily in quality) only to Rod Serling himself. Today’s story, “Little Girl Lost,” was itself adapted by Matheson for a Twilight Zone episode, though I have to admit my memory of this one is foggy.

Placing Coordinates

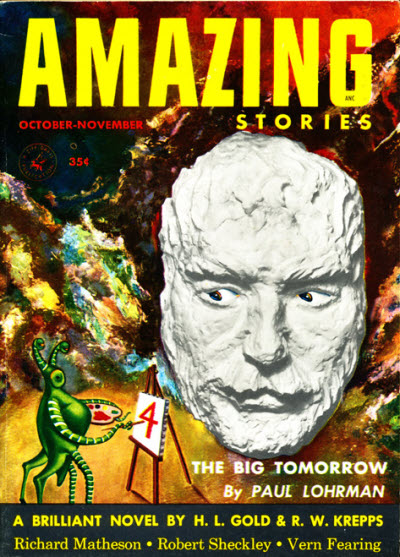

First published in the October-November 1953 issue of Amazing Stories, which is on the Archive. It was then reprinted as a “classic” in the April 1967 issue, which can be found here. It’s been reprinted several times, although not as many as I would’ve thought. The most relevant of the bunch, at least to my interests, would have to be The Twilight Zone: The Original Stories (ed. Martin H. Greenberg, Richard Matheson, and Charles G. Waugh), which, as you can guess, collects the short stories that served as the basis for Twilight Zone episodes. The most recent reprint is Duel: Terror Stories by Richard Matheson, which might still be in print although it’s hard to tell, especially since the quintessential Matheson collection is now Penguin’s The Best of Richard Matheson (which does not include “Little Girl Lost”).

Enhancing Image

Chris and Ruth are a young couple living in a California apartment who one night hear their daughter Tina crying, and like any reasonable man Chris gets up to see what the trouble is. He has to make his way into the living room. “Tina sleeps there because we could only get a one bedroom apartment.” It’s dark, but he can at least hear her. One problem: she’s not on top of the sleeper sofa. Tries reaching under the sofa: she’s not there either. And yet Chris can hear her crying… from somewhere. Tina has to be somewhere in the apartment and yet Chris can’t figure out where she could be. The dog, who’s out on the patio at night, has also started barking like crazy, which doesn’t help. This is a story structured such that it starts off at its most tense and gradually becomes less so, as you’ll see.

Context is important, and we know enough about Matheson to get it. He probably wrote “Little Girl Lost” in early 1953, at which point he was not only a newly married man but father of one (with more to come), and he apparently based the story on struggling to find his daughter one night when she was crying. This is a story about people around my age: a few years out of college, maybe married with their first kid or with one on the way, although Chris and Ruth were not able to buy a house at this point in their lives. I relate to these two, because I also can’t afford a house. Anyway, it doesn’t take long for the young couple to break into hysterics over figuring out where their daughter could’ve gone. She can’t have been abducted, becaue they can hear her, but she’s not in the living room or kitchen, or anywhere else in the apartment they can think of. I heard a criticism somewhere that Ruth is written in the typical “hysterial woman” fashion of the ’50s, but to be fair to her, it would take an iron will to not freak out about this situation, especially if it’s in the middle of the night.

(If you wanna lose some sleep then look up stories about people accidentally locking themselves inside convenience store freezers and being found as corpses in the morning. Have fun with that.)

Chris, instead of calling the police, hits up his friend Bill. “I’d called him because he’s an engineering man, CalTech, top man with Lockheed over in the valley.” Not ideal, but Chris can’t think of a better option in the heat of the moment. Maybe what’s happened to Tina can’t be explained by normal procedure and someone in the sciences ought to be brought in. Because this is a science fiction story and because some of us have seen the Twilight Zone episode beforehand, it’s rather hard to spoil this one. As such, I’ll make a couple more observations before we get into the back end, where there’s not a lot to talk about. This story, after all, is not quite ten pages long and those pages go by at a mile a minute. Matheson’s style is not pulpy but it’s certainly not concerned with fancy language; it goes down smooth, like the average experience of reading a screenplay. I interned as a script reader years ago and the best scripts (or rather the least bad) describe action as economically as possible, with no room given to purple prose antics.

Another thing to consider is that short stories are great for adapting into short films and TV episodes. You may notice that a lot of the shorts comprising Love, Death + Robots are based on short stories, and in those cases the filmmakers can choose to be as faithful to the source material as they want, making the shorts at just the “right” length to cover everything without need for padding. Now, when adapting a ten-page story into a 25-page teleplay, some padding is required. You could easily do the plot of “Little Girl Lost” justice in a short that’s about as long, one page per minute of screentime, but Matheson, when adapting his story for TV, undoubtedly had to make concessions. I don’t remember the Twilight Zone episode too well, but I do remember that structurally it stayed close to the source material; most importantly it retains the climax and tries its best considering it has to work with budget and effects of that era.

There Be Spoilers Here

Eventually the couple let their dog into the apartment, whereupon the dog apparently sniffs out where Tina is and finds what can only be described as a crack in the spacetime fabric that soon sees dog and then Chris fall through it. Chris slips into this other world that’s at once darker than the depths of the ocean and yet filled with blinding lights. “It was black, yes—to me. And yet there seemed to be a million lights. But as soon as I looked at one it disappeared and was gone. I saw them out of the sides of my eyes.” This is undoubtedly the money shot for both short story and TV episode, as we see the mundane apartment replaced with something very different that would strike anyone as alien. The justification for the dimension gap is about as silly as you’d expect, but it at least justifies the story’s escalation into borderline cosmic horror before we earn our happy ending.

The sofa and TV set have now been swapped in the living room so that nobody will be tempted to fall through that crack between dimensions. Call me a zoomer, but I have to look up who Arthur Godfrey is. Actually I’m not ssure if people twenty years older than me know who that is.

A Step Farther Out

It’s short, it’s slight, it’s not exactly deep, but it is evocative and it has imagery in the back end that would translate well to a visual medium. Matheson was a wizard when it came to moving a plot along and while “Little Girl Lost” is simple, it goes down in an even shorter time than its page count would suggest. I was gripped by this extended metaphor for what it’s like to be a young parent and to experience something horrible you’ve probably never thought about before—not until you became responsible for someone’s life. Just remind me to never have kids; a dog sounds better.

See you next time.