Who Goes There?

Theodore Sturgeon was, for one or two spans of time, arguably the best American SFF writer in the business. It can be hard to judge Sturgeon’s career as a whole since he had periods of inactivity, and health problems seemed to prevent him from writing much in the last decade or so of his life; but when he was on the ball, he was on it. Unlike most authors in the pulp days, who tended to specialize in SF or fantasy, Sturgeon was great at both, and sometimes his fiction can be hard to categorize. Sadly he never broke into the mainstream like Ray Bradbury, despite some brushes with notoriety, such as his involvement with Star Trek. (His second episode for the original series, “Amok Time,” is one of my favorites.) He is the one who coined Sturgeon’s Law, although it was originally called Sturgeon’s Rule: 90% of science fiction is crud, but then 90% of everything is crud. This rule, however, does not apply to Sturgeon’s own work. He was, for my money, one of the best short story writers of the 20th century.

The ’50s can be thought of as Sturgeon’s heyday, and 1953 especially might’ve shown Sturgeon at the very peak of his powers. We saw his novel More Than Human, often considered his best (though I think the last third is comparatively weak) and which won the International Fantasy Award; and there were such iconic short stories such as “A Saucer of Loneliness” and “The World Well Lost.” “The Silken-Swift” is not as well-known as those stories, likely because it’s fantasy (which has always had an uphill battle when it comes to short fiction) and a more demanding read. It’s totally possible to read “The Silken-Swift” casually and not understand what’s happening at first. This is Sturgeon’s writing at its most controlled and layered, and unsurprisingly he would later regard it as one of his personal favorites. He wrote it as basically a fairy tale for adults, and it was such a success that it’s still one of the best of its kind. This is a Sturgeon who has reached full maturity as both a person and artist.

Placing Coordinates

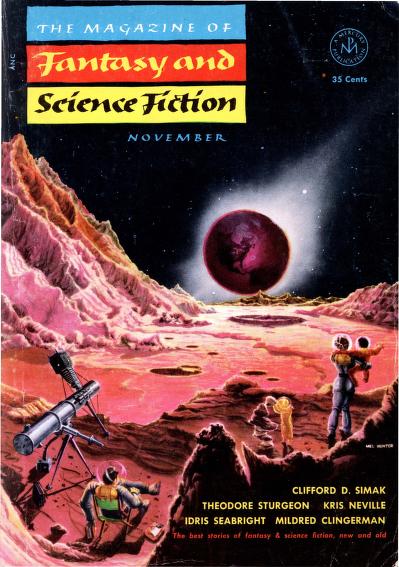

First published in the November 1953 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. In A Saucer of Loneliness, Paul Williams says this story’s magazine publication happened simultaneously with its inclusion in the Sturgeon collection E Pluribus Unicorn, although ISFDB doesn’t give a publication month for the latter. However, the introduction in F&SF says it precedes the collection by a month, with “The Silken-Swift” being a teaser for E Pluribus Unicorn. Where else has it appeared? Unicorns! (ed. Jack Dann and Gardner Dozois), The Fantasy Hall of Fame (ed. Robert Silverberg), Masterpieces of Fantasy and Enchantment (ed. David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer), and The Oxford Book of Fantasy Stories (ed. Tom Shippey), to name a few.

Enhancing Image

The story incorporates a poem not written by Sturgeon, titled “Unicorn.” It was written by Christine Hamilton and seemed to have been unpublished prior to “The Silken-Swift.” Now who is Christine Hamilton, you may ask? I assumed maybe she was one of Sturgeon’s wives or mistresses, but she was actually Sturgeon’s mother, and she was herself a writer, albeit mostly unpublished. It’s cute that Sturgeon would incorporate his mom’s poetry into a story that is ultimately about womanhood—not that Sturgeon considered himself a feminist, as far as I can tell, but he did sometimes write about women’s struggles under patriarchy. He didn’t write about systemic injustice so much as things like hypocrisy and arbitrary restrictions on how women “ought” to live their lives. He seemed to think highly of “The Silken-Swift” among his own works because its theme was (and sadly will probably always be) prescient. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that out of Sturgeon’s heyday, this story might’ve aged the most gracefully.

So, the plot. I won’t get too deep into it, since it’s a dense narrative and there seems to be some confusion (from reactions I’ve seen) as to what actually happens in “The Silken-Swift.” I also had a concussion a few days ago and am still recovering from that, so sadly I won’t be writing about this as much as I would’ve liked. We have three main characters: Rita, a squire’s daughter who lives in a manor; Barbara, a vegetable saleswoman who lives near said manor; and Del, a brash man “whose corded, cabled body was golden-skinned, and whose hair flung challenges back to the sun.” Rita and Barbara live in the Bogs, right outside town, with a “pool of purest water” by the manor; be sure to remember this last part. At the beginning, Del is sort of lured to the manor while the squire himself and the servants have gone out, leaving just Rita, who takes Del in—although not to do with him what he expects. The two have a good time at first, but before Del can get to second base, Rita plays a rather cruel trick on him (she apparently has been toying with witchcraft) by blinding him. Her reasoning is that no man shall have her—that she will remain a virgin so that one day she can catch a unicorn; this is taking teasing to extreme levels, you have to admit.

After Rita’s catch-and-release routine with Del, she kicks him, still blinded, out of the manor, and it’s here that we meet our other female protagonist. It’s also here that Sturgeon does something very strange for a work of prose fiction, although it does tie into the poem at the story’s center: he repeats himself, a whole paragraph, literally word-for-word. We’re introduced to Barbara twice. I had this feeling of recurrence when reading, so I had to copy-paste these two introductions just to see if my brain (which had just been rattled, mind you) was fucking with me.

The first time:

Deep in the Bogs, which were brackish, there was a pool of purest water,

shaded by willows and wide-wondering aspen, cupped by banks of a moss

most marvelously blue. Here grew mandrake, and there were strange

pipings in midsummer. No one ever heard them but a quiet girl whose

beauty was so very contained that none of it showed. Her name was Barbara.

Then the second time:

Deep in the Bogs, which were brackish, there was a pool of purest water,

shaded by willows and wide-wondering aspens, cupped by banks of a moss

most marvelously blue. Here grew mandrake, and there were strange pipings in midsummer. No one ever heard them but a quiet girl whose beauty was so very contained that none of it showed. Her name was Barbara.

This tactic might not work for some people, and it might seem like padding (this is not exactly a long story in the first place), but it fits with what Sturgeon is going for, which is a sort of narrative prose poem. Sturgeon can at times try too hard with his style, but this might be the single best use of poetry (actual poetry on top of poetic prose) in his writing. The setting is definitely medieval fantasy, but aside from the squire’s manor and the elusive unicorn at the heart of the story this feels detached from any one time frame; it doen’t feel like a stereotypical medieval fantasy setting because there’s basically none of the iconography we’ve come to associate with such a setting. The Bogs are a place that could exist, and the three central characters feel like they could be modeled on real people, despite very much fitting into archetypes appropriate for an allegory. “The Silken-Swift” is ultimately an allegory, if a rather indirect one, with a clear message that floats to the surface despite details of the plot being obscured. Simply put, it’s a story that has not aged, which can’t be said for the vast majority of literature, although fantasy does have a much easier time detaching from the circumstances of its making than science fiction.

As for Barbara’s side of the story, this is where people seem to get confused, and admittedly Sturgeon uses some obtuse language to skirt around a horrific event that, if written today, would probably be described in more visceral terms. Something I realized while reading is that Rita and Barbara are like mirror images of each other, to the point where they could be related. They’re similar enough, or at least sound similar enough, that a blinded Del confuses Barbara for Rita; this will turn out to have very bad consequences for Barbara, since Del, having just been kicked out of the manor and not knowing where he is, is out for revenge. Barbara does her best to care for an injured Del (who, as far as she knows, is just a dude who had something bad happen to him), but Del does something. Is it rape? Probably. It happens so quickly and is so indirectly described that you could miss it on a casual reading, which is one gripe I do have with this story (because nothing is perfect): either out of artfulness, getting around censorship, or likely both, Sturgeon’s language can be a little opaque.

Get this:

Once she cried out.

Once she sobbed.

“Now,” he said, “you’ll catch no unicorns. Get away from me.” He

cuffed her.“You’re mad. You’re sick.” she cried.

“Get away,” he said ominously.

Terrified, she rose. He took the cloak and hurled it after her. It almost

toppled her as she ran away, crying silently.

You might not even know something had happened if you’re not reading carefully; but credit where credit’s due, Sturgeon implies a great deal in just a few lines. If Barbara was a virgin before then she apparently isn’t one now. Del does something pretty heinous, but it’s also hard to gauge how in control of his own actions he is, given he’s evidently still under the effects of Rita’s witchcraft and is so delirious that he thinks Barbara is Rita; but also the fact that he wanted to rape Rita in retaliation for the witchcraft is inexcusable. Barbara becomes a victim of Del’s abuse and, more indirectly, of Rita’s treachery; but despite all this she retains her sense of virtue, which is important to remember. Unicorns have often been treated in mythology as embodiments of purity, and indeed associated with purity; in the case of “The Silken-Swift” this purity is assumed to mean one’s virginity. Sturgeon, however, asks a simple question: What really counts as “pure?” Rita thinks herself pure, but she’s also a major bitch; meanwhile Barbara is the victim of sexual assault, yet is no less “pure” for it.

I wanna say the message of the story (because like all allegories it does have a clear message, for all its indirectness of style) is the one way you could date it, but unfortunately the message is evergreen. Women’s “purity” is still obsessed over in practically every major society you can think of, regardless of how authoritarian or libertarian the society’s governing system is, and regardless of the majority religion. Misogyny is always here, and might always be here on a systemic level. Among the many ways trans women are dehumanized is to frame them as sex-hungry monsters who prey on “innocent” cisgender women; and of course there’s no such thing as a “pure” trans person, because if you “violate” gender norms then you have already lost that claim to purity. (Never mind that a truly horrifying number of genderqueer people are victims of sexual assault.) Even some liberal-minded people feel threatened somehow if a women has had “too many” sexual partners in the past—if they aren’t reserved enough for their current partner. Sturgeon says this is all bullshit, and while yes the implication of sexual assault is not kid-friendly, this really is, in its subject matter and complexity, a fairy tale “for grown-ups,” as Sturgeon said of it many years later.

There Be Spoilers Here

I don’t even wanna get into spoilers, honestly.

Read it for yourself.

A Step Farther Out

Earlier in my review I said “The Silken-Swift” has not aged, which is not the same thing as saying a work of literature has aged gracefully. Most literature, indeed most great literature, is firmly rooted in the circumstances under which it was written, whether it be the author’s personal baggage or societal norms of the time and place. This in itself is no disgrace. Dhalgren could’ve only been written in the late ’60s through the post-burnout ’70s. The Crying of Lot 49 could’ve only been written during that short period in the ’60s following John F. Kennedy’s assassination and the Beatles landing in America, but before the Vietnam War escalated. Even fantasy, which tends to be more timeless than other genres, is not always excempt. The Once and Future King was clearly written in reaction to the horrors of the Great War and, later, World War II. But “The Silken-Swift,” in both its conception and its message, is timeless; you can’t put a date or place on it. Sturgeon, despite being most known for his SF, was really more comfortable as a fantasist, and I think this is a prime example of such talent.

See you next time.