Who Goes There?

Charles Beaumont was one of a generation of SFF writers who may have started out in the pulps, but who quickly adopted a style that allowed them to enter the slicks—possibly even attract mainstream attention. Beaumont debuted in the January 1951 issue of Amazing Stories with “‘The Devil, You Say?’,” which he would much later adapt into one of the more iconic episodes of The Twilight Zone, for which he was a prolific contributor. Like Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson, Beaumont played fast and loose with genre conventions, but ultimately one could consider him a horror writer. It should come as no surprise that he would write a few scripts for Roger Corman movies, including an adaptation of his own novel (his only solo novel, sadly), The Intruder. In the ’50s and early ’60s he was one of the best short story writers, and his list of classic stories (“Perchance to Dream,” “The Jungle,” “The Howling Man,” etc.) is impressive.

No doubt Beaumont would’ve kept going, maybe even made his big break as a screenwriter, had a horrific illness (likely a combination of Alzheimer’s and Pick’s disease) not eaten away at his brain in the last few years of his life. He apparently looked and acted like a man who was pushing ninety when he died in 1967, at 38 years old. Beaumont’s early death is surely one of the more tragic losses in the field’s history, made worse because he stopped writing right before the New Wave kicked in. But today’s story, “Free Dirt,” shows a young and hungry Beaumont, arguably at the height of his powers as a short story craftsman. Here we’re presented with a ruthless and ironic horror yarn in the allegorical mode.

Placing Coordinates

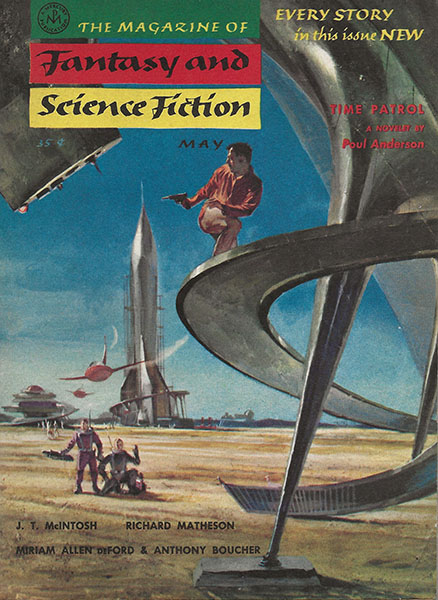

First published in the May 1955 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It has since been reprinted in The Graveyard Reader (ed. Groff Conklin), The Best Horror Stories from the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (ed. Edward L. Ferman and Anne Jordan), and now can be found pretty easily in the Beaumont collection Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories.

Enhancing Image

Mr. Aorta (what an odd name) is a scoundrel. I don’t mean in the sense that he chases after women or loves gambling, but that Mr. Aorta is a cheapskate to the point where he’ll dupe other people into not making him pay for anything. Beaumont set out to write a thoroughly detestable protagonist, but he had a challenge on his hands: making someone utterly loathsome without also making him a rapist or murderer. Now, Mr. Aorta is a thief, but being a thief doesn’t necessarily make you a bad person; rather it’s his devotion to cheating other people out of their dues that makes him a shithead. He sees thievery as like a craft. Consider how he has gotten not having to pay train fare down to a science: “Get in the middle of the crowd, look bewildered, inconspicuous, search your pockets earnestly, the while edging from the vision of the conductor—then, take a far seat and read a newspaper.” He doesn’t seem to have a job, instead living off all but picking other people’s pockets, even going so far as to impersonate a homeless man and ask for change whilst having his own house. You have to admit, this is rather monstrous behavior, and Beaumont does a great job at setting up his loathsome character for failure.

We know Mr. Aorta is greedy by his actions, but also by how he looks: he is described as grotesquely fat. I’m not even sure if this counts as a negative criticism, but I wanted to acknowledge it, since obesity has been used for centuries as shorthand for a few different meanings, though they are by no means exclusive. It depends on context, of course. More often an obese person is framed as being greedy and/or glutenous, especially with a penchant for overeating; more abstractly it can symbolize the infinite wealth-seeking of capitalist industry (when we talk about “fat cats” we’re talking about fat guys in fancy suits chomping cigars). More optimistically it can symbolize happiness or contentedness: Santa Claus is always depicted as rotund and the Buddha is sometimes depicted as quite massive, despite the historic Buddha certainly not having those proportions. In Beaumont’s story, Mr. Aorta is a miser in the truest sense of the word; he is the gold-hoarding dragon on top of the mountain; he is the penny-pinching capitalist taken to almost an unrealistic extreme. I wanna say this kind of fat-shaming is a product of the story’s age, but sadly you and I know fat-shaming continues to be almost a universal quirk of human behavior; even leftists, who really should know better, are not immune to it.

So how does Mr. Aorta get his just desserts? Because even from Anthony Boucher’s introduction we’re told that this is the story of a man who has, let’s say a deeply flawed worldview (that everything not nailed down belongs to him implicitly), and that this man is about to learn a very hard lesson. In that sense “Free Dirt” is nigh impossible to spoil, because both the author and editor allude to the protagonist’s comeuppance at the start. How does Mr. Aorta come to pick up mounds of free (cemetery) dirt by the truckload and what could possibly compel him? Obviously it’s the word on the sign: free. “What is the meaning, the essence of free? Why, something for nothing. And, as has been pointed out, to get something for nothing was Mr. Aorta’s chiefest pleasure in this mortal life.” Mr. Aorta borrows his neighbor Mr. Santucci’s (he has a first name, but I’m omitting it for the sake of consistency) truck and periodically dumps the free dirt in his backyard, where he intends to grow a garden with it. Think of all that free, furtive soil, never mind that it came from a cemetery, pay no mind to that. If this was a realistic story nothing untoward would happen to Mr. Aorta, but because he has the misfortune of living inside a supernatural allegory, he’s about to find out—too late—that he has made a grievous error.

There Be Spoilers Here

The garden scheme works—until it doesn’t. The free dirt bears Mr. Aorta vegetables until it stops, until the garden starts to degenerate. Desperate, he goes from taking cemetery dirt that was on offer to straight-up grave-digging—not graverobbing, but taking soil from dug but unoccupied graves in that cemetery. Little does he know he’s also digging his own grave. One night, in the backyard, his garden having been obliterated, he sees a solitary reminder of what his scheme was supposed to produce. “A white fronded thing, a plant, perhaps only a flower; but there, certainly, and all that was left.” He reaches for the flower, but soon finds himself at the bottom of a pit, just deep enough (and Mr. Aorta being physically weak enough) that he can’t quite get out of it. The comes the kicker: God has his vengeance. The flower, just out of his reach, now resembles “a hand, a big human hand, waxy and stiff and attached to the earth.” Then the dirt starts being piled on him. It’s a nasty way to go, being buried alive, but it’s about to get weirder.

Enough time has passed without word from Mr. Aorta that Mr. Santucci becomes concerned, despite not being exactly fond of the man. He turns out to not be in his garden where we would expect, but in his dining room—dead. Mr. Santucci and his wife think he had simply eaten until his stomach ruptured, but the autopsy finds that Mr. Aorta’s stomach is filled—several pounds’ worth, maybe—with dirt. How could he have eaten that much dirt, or indeed more than a little of it? The idea of choking on dirt is horrifying enough. But then if he died in the garden like we were led to believe then how did he get back inside his house? These are troubling questions and Beaumont’s not giving us the answers. “He tried to get rid of the idea, but when the doctors found Mr. Aorta’s stomach to contain many pounds of dirt—and nothing else—Mr. Santucci slept badly, for almost a week.” Clearly we’re not supposed to expect a realistic or plausible answer, but simply to accept that the dirt is somehow cursed and that God (or some other power not to be toyed with) has reaked vengeance on Mr. Aorta. It’s an allegory—a fairy tale about a man being undone by his own greed.

A Step Farther Out

It’s been a few days since I had read this story (bit of a long explanation), so the visceral discomfort I felt with the ending has since softened. With that said, its effectiveness is undeniable. The style is indicative of slick fiction of the ’50s, and in that sense it shows its age, but with a bit of finesse it could feasibly be published today. Beaumont seemed preoccupied with the inner darkness of man, whether it be greed or the inability to connect with one’s brethren, and “Free Dirt” is a succinct example of Beaumont as a moralist—not the good-tempered Sunday school teacher but the righteous vengeance of the Old Testament God.

See you next time.