Who Goes There

Brian Stableford started out as a fan, and even made his professional debut while still a teenager back in the ’60s. His early start implied a fierce intellect, which he would then go on to vindicate by contributing to the field in several disparate ways—all of them rather intriguing. He was an author, sure, but he was also a prolific translator, possibly being the person most responsible for bringing modern French SF to an English readership; and on top of that he was an editor and genuine studier of the field, even contributing to the SF Encyclopedia. If you’re like me and you like to dig through genre history then you’ve very likely already gotten a taste of Stableford’s writing, if not necessarily his fiction. It makes sense, then, that today’s story is all about history—family history as well as genre history. It’s tempting to call “The Growth of the House of Usher” an Edgar Allan Poe pastiche, but that isn’t quite right. Does it live up to its famous namesake? Hmmm. Almost. Stableford made a solid go at it.

Placing Coordinates

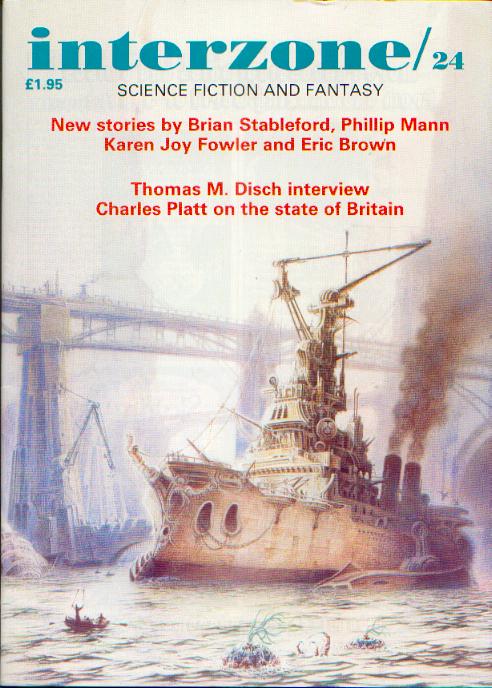

First published in the Summer 1988 issue of Interzone, which for some reason is not on the Internet Archive. Most of Interzone‘s back issues up to like 2010 are on there, but not this one. It is on Luminist, but… whether I provide a link to Luminist depends on what mood I’m in. Like what even is it? Some weird new age thing? Anyway, this story was then reprinted in The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Sixth Annual Collection (ed. Gardner Dozois), Interzone: The 4th Anthology (ed. John Clute, Simon Ounsley, and David Pringle), and the Stableford collection Sexual Chemistry: Sardonic Tales of the Genetic Revolution.

Enhancing Image

It’s impossible to talk about this story without also talking about Poe’s, which I’ve read several times over the years and which I just (as I’m writing this) finished rereading it. So consider this a review and a half. Needless to say I’ll be spoiling both, although the Poe story is so famous that unless you live under a rock you already know the broad strokes of that one. I’ll be spoiling the Poe story early and with extreme prejudice.

Immediately there are some parallels. The unnamed (in both cases) narrator travels (by motorboat in the Stableford, by horse in the Poe) to the secluded manor of his friend whom he has not spoken with in years, Rowland Usher. Rowland is the last of the Ushers, a sickly man who never married or had offspring, and who evidently is grieving over the death of his sister. In the Poe, the sister (Madeline) died very recently, such that Roderick and the narrator are able to place her still-warm body in the family vault. (Turns out she’s not as dead as she appeared.) Unlike her Poe counterpart, though, Rowland’s sister (Magdalene) is super-dead; in fact she died several years prior to the story’s beginning, as a teenager. Not everything lines up, much to the narrator’s relief. “I think I might have been alarmed if Rowland had told me that his sister were still alive, and had I seen her flitting ethereally through the apartment just then. This would have been one parallel too many for my tired mind to bear.” But still, Rowland is dying, and has called on his old college friend to hear his last will and testament—and to understand the very odd experiment that is the Usher house.

“The Growth of the House of Usher” is very much a recursive story, probably even more so than the usual, in that not only does it openly take after a classic work, and not only does it expect the reader to already be familiar with the story it’s taking after, but the characters within the story are also aware that they’re inside a recursive tale. Rowland Usher had intentionally modeled the house after the Poe story, although interestingly more as a response to it than out of sheer respect. The new Usher house is also, in a weird way, alive. Rowland’s been a devotee of biology for years; it runs in the family. He’s been using this knowledge to run experiments, with his own house as what he hopes will be his finest achievement. This fixation on biology might come from the fact that the Ushers have been afflicted with a hereditary illness akin to cancer that’s now whittled their numbers down to one man. The women in the Usher family took this illness worse than the men, dying in the teens like Rowland’s sister did. In the Poe story, the physical defects in Roderick and his sister are implied to come from acute incest—the Usher family tree being less like a tree and more like a long blade of grass. Similarly Rowland and his sister were also in an incestuous relationship, although this is made explicit rather than implicit, with the narrator admitting that by the 22nd century the taboo against sibling incest had become more or less a non-issue.

Let’s talk about incest some more, since it figures so heavily into the basic “Usher” narrative, both literally and symbolically. Something to keep in mind about when Poe lived, in the first half of the 19th century, consensual incest was by no means uncommon—so long as it was between cousins. It was a regular practice in the US and UK, among the aristocracy and even in lower-income households. Poe himself was betrothed to his cousin Virginia, and while there’s been debate for decades as to whether the couple ever “consummated” or if it was more platonic, a) to think the couple’s relationship was not even romantic would be wishful thinking on the part of puritans, and b) the fact is that from we do know, Poe very much loved Virginia, and was stricken when she died—possible driven to despair. And yet one has to admit that “The Fall of the House of Usher,” arguably Poe’s greatest story and undoubtedly his biggest contribution to the Gothic tradition, is strangely transfixed on the prospect of a family being undone by long-term incest—even if said incest is only alluded to. Poe and Virginia had been married for a few years, with Poe only pushing thirty when he wrote “Usher,” and yet despite Virginia’s tuberculosis diagnosis still being a few years off it’s a story all about sickness. Of course, if you’ve read enough of Poe’s fiction then you start to figure he was always kinda Like That™, being obsessed with the sickly and morbid.

Poe’s influence on Stableford’s story is so strong that even the narrator talks in a way that mimic’s a typical Poe narrator, although it’s unclear if this pseudo-Victorian manner is just a quirk the narrator and Rowland have or if it had somehow become in vogue for educated Americans in the 22nd century, since there are basically no other human characters to speak of—at least none currently living. It’s also possible that reading a ton of Poe, Byron, and other Romantic-era writers during his stay at the Usher house had an influence on the narrator’s speech, since by his own admission he has started to even dream of Poe-esque terrors. “I—a scientist of the twenty-second century—was infected by the morbidity of the Gothic Imagination!” To make matters worse, the narrator catches a glimpse one night of a young and for some reason naked girl, “fourteen or fifteen,” coming out of Rowland’s bed chamber, but doesn’t get the chance to intercept her before she makes off into the night. In fairness to the narrator, he’s not even sure if this is really happening at first, and anyway it’s certainly hard to explain. Could this be Rowland’s dead sister? But Magdalene died years ago; even if she were still alive somehow she would be visibly older than this. It’s also this aspect of the story where I think Stableford goes too far, or rather he goes far without a constructive reason behind the transgression that I can discern. I had heard this story contains “creepy sex stuff” and I’m pretty sure the “stuff” with the teen girl is what’s being referred to here.

Since “The Growth of the House of Usher” is all about biology and genetics, it must also—by extension if nothing else—be about sex. This is a dangerous game for writers, especially SF writers. Prior to the ’50s there was almost no discussion or even mentioning of sex in genre SF (I say “the ’50s” and not “the ’60s” because, as a devotee of ’50s SF, I can tell you that authors at that time were often incredibly horny, only they didn’t show it in as crass a language as the New Wave folks), and so in the years following the laxing of censorship some authors took it upon themselves to go maybe too far in the other direction. The ’70s were an especially bad time for this sort of thing (read twenty post-New Wave SF stories at random and take a shot every time there’s a dubious relationship between a grown-ass adult and a teenager), marring what in some cases would otherwise be great fiction. I find it interesting that Stableford would turn the subtext of Poe’s “Usher” into text while also flipping the house of Usher itself on its head by turning a deeply unnatural work of architecture (indeed a house that’s implied to have its own genius loci) into a house that is made up of thousands of living organisms—a house that quite literally lives and breathes. At the same time the subplot with Rowland’s sister a) doesn’t quite mesh with the ambitious genetic engineering of the house, and b) almost smacks of wish-fulfillment rather than contributes to the psychology of the narrative. It enters a level of creepy that Stableford probably hadn’t intended.

There Be Spoilers Here

Being faced with the immanent death of himself and his bloodline, Rowland has put his research into building something that won’t sink into the swamp like Roderick’s mansion—indeed a living construct which will, with time, grow to even more extravagant heights. The house “was greater than ten thousand elephants, and that if it had been a single organism then it would have been the vastest that had ever existed on Earth.” It’s a wonder of the world, a marriage between genetics and engineering that, so we’re told at the very end, has only grown since Rowland’s death. And Rowland does die, unfortunately, on the night he tells the narrator all about his family history, his relationship with his late sister, the ways in which their father treated them as “guinea-pigs,” and what he hopes for the future—a future he knows he won’t be a part of. The narrator tries to take care of his friend’s affairs after his death; it’s not like Rowland had a next of kin to do this. Oh, and then there are the “mayflies,” which from what I understand are insectoid beings who appear human, indeed have DNA shared with Rowland’s late sister and thus resemble her. I don’t like to think about that, because it’s very weird, and not in a good way. I wish Stableford was still alive so I could ask him what he could’ve possibly meant by this. Like what was bro cooking? Again the weird stuff mars what is otherwise a good ending.

A Step Farther Out

I liked it for the most part, although part of that might be my love of Poe and genre history—loves which Stableford happens to share. I probably should’ve mentioned at the beginning that “The Growth of the House of Usher” spawned from a speculative non-fiction book Stableford wrote with David Langford, The Third Millennium: A History of the World AD 2000-3000, which would serve as the basis for a future history called the Biotech Revolution. “The Growth of the House of Usher” was the first story written for this future history, although what stories exactly are part of this future history is unclear since there’s not a complete overlap between stories included in Biotech Revolution collections and what ISFDB counts as part of the series. It’s a bit complicated, but it’s also intriguing.

See you next time.

One response to “Short Story Review: “The Growth of the House of Usher” by Brian Stableford”

I reviewed all of Stableford’s Biotech stories and novels — mostly in their order of publication.

Stableford was a great admirer of Poe and wrote a series of novels — strange mixtures of the occult and philosophy and science and even the Cthulhu Mythos — with Auguste Dupin.

LikeLike