Who Goes There?

While never quite breaking into the mainstream like Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson clearly copped a few notes from the Bradbury notebook and, over time, became one of the more accomplished authors in the field. He debuted in 1950 with “Born of Man and Woman,” which despite being written when he was 22 or 23 remains one of his most famous stories. He quickly amassed an impressive body of short fiction, but it was his 1954 novel I Am Legend that remains his most famous work, being one of the few truly influential depictions of vampires to come out of the 20th century. His other major novels include The Shrinking Man, Hell House, and Somewhere in Time, but it’s his efforts as a short story writer and screenwriter that hold my attention the most. He wrote the short story and screenplay (I’m not sure which came first) for Duel, Steven Spielberg’s first movie. He was the second most prolific writer for The Twilight Zone—only behind Rod Serling, of course. Unlike close contemporary and fellow Twilight Zone writer Charles Beaumont, he lived to see much recognition in his lifetime.

“Steel” was itself turned into a Twilight Zone episode, adapted by Matheson, with Lee Marvin as the lead; it’s one of the better episodes in the original series, I would say. If you’ve seen the episode (as I have) then you’ve already seen the story told in the source material, albeit compressed. Unsurprisingly Matheson did not stray much from his own story. Unlike “Little Girl Lost,” which I reviewed before and which Matheson also turned into a Twilight Zone episode, I’d consider “Steel” to be major Matheson. I’m not sure why it has been reprinted relatively few times.

Placing Coordinates

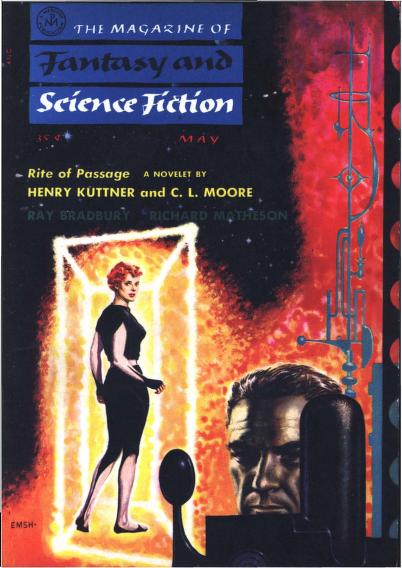

First published in the May 1956 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It later appeared in The Twilight Zone: The Original Stories (ed. Martin H. Greenberg, Richard Matheson, and Charles G. Waugh) and the collections Duel: Terror Stories by Richard Matheson and Steel and Other Stories. That last one seems to be a tie-in for the movie Real Steel, which is a much looser adaptation than the Twilight Zone episode. Yeah, “Steel” has been adapted more than once.

Enhancing Image

The premise is simple. It’s the year 1980, and human boxers have been replaced by human-like robots for several years now. We follow Kelly, his mechanic friend Pole, and their fighting robot Maxor. Unfortunately Maxor is a B-two, out of date for a few years now what with B-nines set to release, and he’s barely holding together at the seams.

“The trigger spring in his left arm’s been rewired so many damn times it’s almost shot. He’s got no protection on that side. The left side of his face’s all beat in, the eye lens is cracked. The leg cables is \vorn, they’re pulled slack, the tension’s gone to hell. Christ, even his gyro’s off.”

The three have traveled far for a match, and while they’re set to get an amount of money for even one round in the ring, Maxor might fall apart before he can land a single punch. Kelly himself used to be a boxer, before the robots came in, but he’s middle-aged now, balding, and reminiscing on his glory days. “Called me ‘Steel’ cause I never got knocked down once. Not once. I was even number nine in the ranks once,” he says. When they finally get to the prep room and Maxor has a major malfunction, Kelly’s left with seemingly no options: if his robot doesn’t work then he and Pole don’t get paid at all and they return home with their tails between their legs. Doesn’t help the two have been pretty tight on money. However, Kelly reasons, the robots already look uncannily similar to real humans, and because these are pre-internet days and because Maxor’s been out of the limelight for a minute, nobody in the crowd is likely to recognize him. Kelly comes up with a crazy idea, but with some finesse it just might work.

Let’s talk about sports a bit. I’m supremely indifferent sports, even e-sports despite being a Gamer™ and despite having been a wrestler for nearly a decade. I was that strangest of amalgamations in middle school through most of high school: the nerd-jock. I was an athlete but also a late bloomer when it came to reading, and I had to make due with a rare eye condition, scoliosis, and (very likely) autism. It takes some fine storytelling for me to get into a sports narrative, and yet I have to say of all the sports subjects, boxing might have the easiest time with this, being closest kin to wrestling, a deeply intimate and individualistic sport. It probably helps that boxing has been blessed with some of the best fictional depictions in film and literature, from Rocky and Raging Bull to Leonard Gardner’s Fat City. The trend continues with “Steel,” both the story and the Twilight Zone episode. I’m not sure if Matheson is a fan of boxing (he’s almost certainly not an expert), but that doesn’t matter because this is a story about one man who, whether he knows it or not consciously, desperately wants to relive his glory days—to feel like the toughest man in the world again.

At the same time it’s about the need for the human element in sports, and how replacing the human spirit with robotics is no adequate substitute. For decades, indeed since the 19th century, there’s been a fear, especially among the working class, that automation will replace human labor and that humans may even be forced to train the machines that will leave them out of a job. I was scrolling through copy-editing positions the other day (I’m looking for a second job at the moment) and I saw a couple that were for some AI company, wherein the position called for competent human writers to spend hours tinkering with chatbots so that these machines can write coherent sentences. They want people to come in and train simulacra to do their own jobs for them. Obviously this will not do, for a number of reasons. Even in the world of “Steel,” while boxing between robots is popular, there are limitations: the models up to now are unable to even get back on their feet if they’re knocked down. “A felled B-fighter stayed down. The new B-nine, it was claimed by the Mawling publicity staff, would be able to get up, which would make for livelier and longer bouts.” The people want robots, but what they truly want is the real deal.

(As a random note, I find it slightly funny that Matheson, for no discernable reason, moved the year down from 1980 to 1974 when writing the Twilight Zone script, despite the episode airing in 1963—just over a decade before it’s set to take place. Obviously Matheson could not have possibly expected lifelike robots to not only be invented but replace human participants in sports by then. It’s a good thing science fiction is meant to comment on the perpetual present moment rather than predict the future, contrary to what a lot of people seem to think.)

Matheson gets a lot of work done in about twenty pages: he introduces a future America that’s different but not too different, a friendship between two guys that goes back years, a whole history of one of the guys as a former athlete, and a tense do-or-die sports narrative. You don’t have to be into boxing to find enjoyment or meaning in it, which I’d argue goes the same for any sports writing: it should be able to engross someone who previously had next to no interest or knowledge in the sport. We know a fight’s coming, and admittedly the fight in the story’s climax is the least engrossing for me personally, but a) that’s not the point, and b) it’s a personal thing of mine when it comes to action writing, so I’m not holding it against the story too much. I knew where things were going in advance, and while I wasn’t surprised at any point, that’s not a fair criticism to make from someone who had already seen a faithful adaptation. My point is that Matheson is often good, and when he’s good he’s great.

There Be Spoilers Here

The ending is bittersweet, although how bitter or sweet you think it is depends on how much you believe Kelly’s optimism. He poses as Maxor and predictably gets his ass beaten—almost killed, actually. It’s amazing he survived, going up against a robot made to fight other robots, and even more amazing the ruse worked. Kelly and Pole only get half the money they were owed since Kelly went down in the first round, but again, Kelly got away with the bamboozle, he got some money out of it, and, if only for a minute (possibly the longest minute of his life), he got to feel like a boxer again. Obviously Kelly is too injured to try such a stunt again, and they only got enough money for bus fare and to repair the outdated Maxor; but who knows, people have come back from worse than this. I personally see it as a triumphant ending, despite Kelly’s initial dismay at the low payment, because it’s a spiritual victory for Kelly, even if it’s not quite what he wanted. The former boxer has, for a brief moment, snatched his passion from the jaws of automation; and this can only be a victory.

A Step Farther Out

There’s a reason “Steel” has been adapted multiple times now, and that’s because it is fundamentally a well-done—one might even say well-oiled machine of a short story. It’s structurally sound, has a beginning, middle, and end, has a small cast of characters we can readily identify with; and perhaps most importantly, at least according to what Theodore Sturgeon thought constituted a great SF story, it poses a question about the human condition that would not be possible without an SFnal element in the equation. It’s about nostalgia, in a way, but it’s also about alienation, in both the general and Marxist senses of the word—about the need to feel connected with one’s own labor. Even ignoring all of this, paying no attention to its possible meanings, it’s just a fun read ultimately.

See you next time.