It’s the first editorial of the year, and yeah, I know it’s a bit late to be seeing this. Clark Ashton Smith’s birthday is January 13, so a couple days ago. He was born in 1893 in California, and he would more or less live there for the rest of his life. He never ventured too far, and in the ’20s and ’30s he would care for his ailing parents, hence his turning to writing fiction. So the story goes. Smith never gave interviews, and we still don’t have a biography of him, but we do have copious letters he wrote to H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, August Derleth, and others. With only one serious rival (whom I’ll get to), Smith was, for my money, the best line-for-line writer to appear in Weird Tales during its 1930s heyday; and he appeared in that magazine A LOT. Despite being formidable in both quality and quantity, though, Smith is somewhat forgotten today unless you’re a weird fiction enthusiast; certainly he lacks the mainstream recognition of Lovecraft and Howard. You’d be hard-pressed to find Clark Ashton Smith studies in academia and you’d be as hard-pressed to find Clark Ashton Smith fanclubs.

How Smith’s reputation failed to pick up a posthumous second wind like what happened with Lovecraft and Howard is a mystery that has a few clues, but after all it might not even be a mystery. Certainly Smith becoming semi-obscure by the time of his death is the same fate that befalls most authors—those, anyway, who garnered any reputation in the first place. It’s the singing quality of his prose and the striking power of his writing that makes this fate seem unjust, though. This dissonance between his deserving recognition and not getting said recognition was solidified by Smith “winning” the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award in 2015, an award reserved for authors whom the folks at Readercon believe to be worthy of recovering from the dust piles of history. Even Lovecraft agrees with me and the Readercon people: he singles out Smith as one living master of weird fiction in his seminal essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.” It’s funny, because in some ways Lovecraft and Smith were very different, the former zeroing in on a rather niche subgenre of horror while the latter was content to hop across genres if it meant an extra paycheck.

Going back to the beginning, Smith tarted out as a poet; as a teenager he caught the attention of some notable personalities in the local California literary scene, even running into Ambrose Bierce. Smith was an autodidact who accrued an enormous amount of knowledge and even learned a couple extra languages from being a voracious reader. He would read encyclopedias and dictionaries front to back. He read seemingly everything he could get his hands on. Even without a proper education, Smith would come to have a much larger vocabulary than the vast majority of people who read his stories in the pulps, hence his (in)famous prose style. Smith dabbled in short fiction during his early days as a poet, but it was not until the late ’20s that he went full steam ahead on writing short fiction. Smith wrote something like a hundred short stories between 1929 and 1934—enough for a lifetime, compressed into five years. All told, Smith put out more fiction than Lovecraft (who, incidentally, did not write a whole lot during that same period), and he probably matched Howard in productivity for a short time there. He appeared in ten out of twelve issues of Weird Tales in 1934 alone, making him an almost omnipresent force.

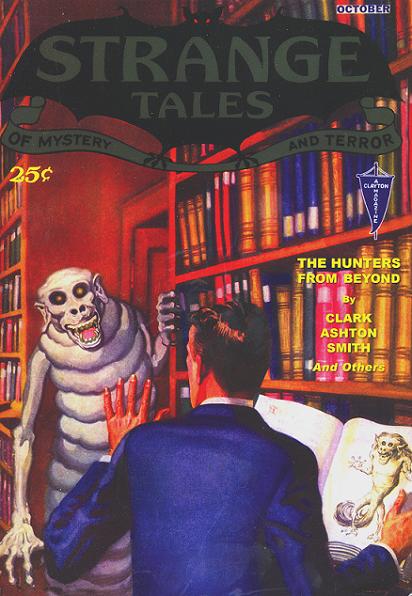

Unlike Lovecraft, who turned up his nose at anything he deemed less dignified than Weird Tales (he was apparently cross when August Derleth sold At the Mountains of Madness to Astounding Science Fiction), Smith was not so picky; he would sell to Weird Tales the most, but he also appeared in Wonder Stories, the short-lived Strange Tales, and even Astounding. Of course, given how much he was writing, Smith could not afford to sell to only one outlet. And unlike Lovecraft, who didn’t seem to think of some of his work as science fiction, and Howard, who straight up never wrote science fiction, Smith was fine with playing into the recently founded pulp SF market, hence his appearing in Wonder Stories almost as often as Weird Tales. Smith had created several series, although it would be more accurate to call them settings: Zothique (a far-future wasteland which anticipates Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth), Hyperborea (a prehistoric Earth not dissimilar from Howard’s fantasies), and Averoigne (an alternate medieval France that has been infested with vampires, ghouls, and the like) are the big ones. When not setting his fiction on some fantastically altered Earth, Smith sometimes resorts to picking Mars or some other planet as the venue.

It’s worth mentioning, of course, that while Smith did play to the expectations of pulp readers for the sake of a paycheck, he did not do much to dumb down his language even with his most uncharacteristic work, which must’ve come as a shock to many at the time. The reality is that even many of the “classic” SF stories of the ’30s are semi-literate; they had other redeeming qualities, but you did not go to such fiction expecting to enjoy the prose for its own sake. Those who complain about the lack of literary flashiness in pre-New Wave SF writing would scarely survive a bout with SF as published in the pulps circa 1934. Read a randomly picked Smith story, on the other hand, and you’ll notice two things: you’ll find at least one word you do not recognize, and you’ll probably get swept up in the rhythm of Smith’s style. I’m a highly colloquial writer as opposed to a poetic one, so rather than try to lecture on what makes Smith’s prose different, I’ll simply provide a couple examples. The first is from the most recent story of his I’ve reviewed, “The Door to Saturn.” The wizard Eibon has used a magical door, courtesy of the god Zhothaqquah, to escape a pack of zealots, and upon entering Saturn (Cykranosh) encounters a strange creature:

He turned to see what manner of creature had flung the shadow. This being, he perceived, was not easy to classify, with its ludicrously short legs, its exceedingly elongated arms, and its round, sleepy-looking head that was pendulous from a spherical body, as if it were turning a somnambulistic somersault. But after he had studied it a while and had noted its furriness and somnolent expression, he began to see a vague though inverted likeness to the god Zhothaqquah. And remembering how Zhothaqquah had said that the form assumed by himself on Earth was not altogether that which he had worn in Cykranosh, Eibon now wondered if this entity was not one of Zhothaqquah’s relatives.

The second example is not from a story I’ve reviewed, but one I had read over a year ago which helped make me a Smith fan. This is from “The Dark Eidolon,” one of Smith’s best and most bombastic stories—a real scorcher of a tale, a dark fantasy epic in miniature. The wizard Namirrha, having accrued an unspeakable amount of power in his decades-long quest for revenge, has summoned the literal horses of the apocalypse to decimate the city of Ummaos, reveling in the destruction even as it will likely cost him his own life in the process:

Like a many-turreted storm they came, and it seemed that the world sank gulfward, tilting beneath the weight. Still as a man enchanted into marble, Zotulla stood and beheld the ruining that was wrought on his empire. And closer drew the gigantic stallions, racing with inconceivable speed, and louder was the thundering of their footfalls, that now began to blot the green fields and fruited orchards lying for many miles to the west of Ummaos. And the shadow of the stallions climbed like an evil gloom of eclipse, till it covered Ummaos; and looking up, the emperor saw their eyes halfway between earth and zenith, like baleful suns that glare down from soaring cumuli.

This shit is EPIC.

I wish I had something more sophisticated to say, but Smith’s work at its best conveys a sense of scale and a dark majesty in the span of twenty to forty pages that most novels fail to match up with, let alone other short fantasy stories of the time. Robert E. Howard was unlikely to use “somnolent” and almost certainly never used “somnambulistic,” let alone in combination with “somersault,” achieving the effect Smith pulled here. Lovecraft was also one to pull obscure words out of his ass, but he also never wrote a story featuring (among other things) a revenging sorcerer, an army of giant skeletons, and horses the size of skyscrapers which trample a whole city underfoot; and this is all in the same story! I’m just saying, read “The Dark Eidolon,” it kicks ass. You could say Smith dared to kick ass in a way Lovecraft had no interest in, and which Howard could only match via a different school of writing, that being the propulsion of action writing. Howard thrilled us with tales of musclebound men fighting demons and giant snakes, rescuing damsels and the like, but Smith thrilled us with his use of language. Reading a lumbering Smith paragraph, with its parenthetical asides and protracted sentences chain-linked with semi-colons, peppered with words you might not have ever seen before but whose meaning you can gather from context, can be like reading an incantation in a forbidden spell book. If Howard was a literary swordsman, then Smith was a literary sorcerer.

There is, of course, at least one writer in Weird Tales in the ’30s who I think matched Smith on almost the same wavelength: C. L. Moore. Being nearly twenty years Smith’s junior, Moore was very young when she hit the scene in 1933, but her first professional story, “Shambleau,” was an immediate success, and in just a couple years Moore garnered a reputation as a sort of prose poet, never mind a writer of immense depth. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry is one of the most memorable old-school sword-and-sorcery characters (she should by all rights be as influential as Conan, but sadly she is not), probably a bigger achievement than any of Smith’s characters individually (although Eibon and Maal Dweb are very fun and dastardly sorcerers), and despite her youth she could at times go toe-to-toe with Smith’s poetic strength. Imagine being a Weird Tales reader circa 1934 and seeing both Moore and Smith’s names in an issue’s table of contents. Both of these writers, for the rather brief time they were direct contemporaries, must surely have expanded the language of many readers, and by extension their minds. Moore is another writer who deserves to be popular with modern readers and for some reason is not; but that is a story for a later date.

Aside from being pessimists with a penchant for penning brooding passages, Smith and Moore were also both more open go writing about sex their most of their contemporaries—I don’t mean sex as a source of titillation, but as it pertains to human psychology. Lovecraft was probably asexual, and so avoided the topic when he could, and Howard, while he did sometimes write about erotic love (never mind his attempts at titillating the reader), was not given to jealousy, forbidden lust, and other psychosexual matters. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry experiences a crisis of conscience when she realizes (after she has killed him out of vengeance) that she is profoundly attracted to the man who had sexually assaulted her. Smith’s characters likewise are at times met with these conflicts between mind and flesh. Jealousy and temptation are especially common. I’ve noticed, after reading enough of his fiction, that Smith was fond of using flowers as symbols for two things at the same time: an ideal and tempting beauty, and a horrific malice which lurks under said beauty. For example, in his story “Vulthoom” (review here), the protagonists are met with an eldritch being in the Martian underground who, seemingly in an effort to tempt Our Heroes™ over to its side, takes on the appearance of an androgynous beauty within a massive flower. Much like Smith himself, who was a notorious womanizer (he only married after his sixtieth birthday), characters in Smith’s writing think about sexual attraction, and this thinking-about-sex plays into their psychologies.

Why did Smith never pierce the mainstream consciousness? There are a few reasons for this. For one, the fact that he never wrote a novel in adulthood (he did write one as a teenager, but it was only published decades after his death and I don’t know anyone who cares to read it), does hurt him, as it would anybody. Unfortunately novels have always sold far more than short stories; you’ll find many stories of SFF writers in the ’50s who take up novel-writing in an effort to make that extra cash. Even Howard, who died so young, wrote a novel with The Hour of the Dragon. Another is that while Lovecraft and Howard were very good at writing a certain type of story, Smith is harder to pin down—that is to say it’s harder to come up with a single “encapsulating” Smith story to hand off to some newcomer. Someone curious about Lovecraft would do well to start with “Dagon” or “The Rats in the Walls,” but an unaccustomed reader might find the sheer awesomness of “The Dark Eidolon” or “The Maze of the Enchanter” off-putting. Even when compared to Lovecraft, who by no means was a slacker in the language complexity department, Smith’s prose is positively purple. The truth is that Smith is at his best when his language is at its most pyrotechnic; an “easy-to-read” Smith story is a relatively boring one. Lastly, Smith was not exactly an innovator, nor did he write extensively on the history of weird fiction; as such he was neither a pioneer nor chronicler of the form.

As you know, Smith’s output slowed to a trickle after 1934; once his parents died he no longer had the financial strain that had pushed him to try writing for a living. He could be coaxed to write a short story now and again thereafter, and strictly from a modern perspective it might seem like he actually wrote a decent amount after 1934. He always remained a poet. Being restless as an artist, he would also take to sculpting and illustrating, although his reputation stands on his prose and poetry. Smith died in 1961, having outlived some of his contemporaries by a good margin, but in the context of weird fiction and American fantasy it’s easy to think he had “died” around the same time as Lovecraft and Howard. Much like how Moore’s story as a writer basically came to an end with the death of her first husband, Henry Kuttner, Smith’s winding-down as a writer of some of the darkest and gnarliest (and at times funniest) fantasy can be said to coincide with Weird Tales‘s subtle decline towards the end of the 1930s. Many writers have tried (and a few have even succeeded) to sound like the next H. P. Lovecraft, but I don’t know anyone who has tried to sound like the next Clark Ashton Smith. Maybe he was a sorcerer without an apprentice.

2 responses to “The Observatory: Clark Ashton Smith, Literary Sorcerer”

“Smith’s work at its best conveys a sense of scale and a dark majesty in the span of twenty to forty pages that most novels fail to match up with, let alone other short fantasy stories of the time. […] Reading a lumbering Smith paragraph […] can be like reading an incantation in a forbidden spell book.”

Apart from your use of “lumbering” I couldn’t agree more. A graceful lumber at the very least. Or a melliferous lurch, which is not to lumber at all!

LikeLike

I’ve enjoyed my limited exposure to his work so far. I look forward to more.

LikeLike