Who Goes There?

Carol Emshwiller came a bit late to the whole writing-fiction thing, not even writing her first novels until she was in her sixties, but she would have one of the longest and most acclaimed careers of any modern SF writer. She started in the mid-’50s and remained more or less active until her death in 2019; the crazy part is that she would remain a high-quality writer over that sixty-year span. She steppd away from writing for much of the ’60s but returns just in time to contribute to Dangerous Visions, with one of its better stories, “Sex and/or Mr. Morrison.” Despite having started in the ’50s, Emshwiller changed her colors like a chameleon and fit right in with the New Wave crowd—and then changed again for the post-New Wave years. This is a degree of versatility most writers couldn’t manage.

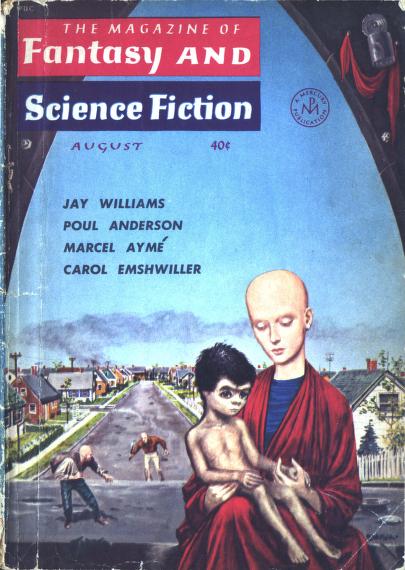

I should probably mention at this point that Carol was the wife of legendary illustrator (later experimental filmmaker) Ed Emshwiller. Yeah. In one of the cuter instances of both halves of a couple being successful creative types, Ed sometimes illustrated Carol’s stories, including the cover depicting “Day at the Beach” that you see above. (It would have to be the cover because F&SF made it a policy to not have interior illustrations for stories.) “Day at the Beach,” while short and simple in a way, has enough evocative imagery that such a cover might’ve been earned; you could do a lot worse than this one. It’s a post-nuclear fable that reminds me of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, in its grimness but also its central message.

Placing Coordinates

First published in the August 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It was reprinted in The Year’s Best S-F: 5th Annual Edition (ed. Judith Merril), An ABC of Science Fiction (ed. Tom Boardman, Jr.), Future Love: A Science Fiction Anthology (ed. Victoria Williams), Beyond Armageddon: Twenty-One Sermons to the Dead (ed. Martin H. Greenberg and Walter M. Miller, Jr. [?!]), and the Emshwiller collection The Collected Stories of Carol Emshwiller Vol. 1. Unfortunately, if what I’ve heard is true, the proofreading for that last one is really bad.

Enhancing Image

We meet Myra, a housewife who has “neither eyebrows nor lashes nor even a faint, transparent down along her cheeks.” She is in fact totally hairless, and so is her husband Ben. Their son, named Littleboy, is however a different story, being “the opposite of his big, pink and hairless parents, with thick and fine black hair growing low over his forehead and extending down the back of his neck.” Littleboy is three-and-a-half years old and we’re told that things were normal not long before then, when nuclear war broke out; it’s implied Littleboy was in utero when Myra and Ben got a generous dose of radiation. Emshwiller is light on the details: we’re never told who fired the first shot, which countries went to war (although we can guess(), or how much of civilization is left after the fallout. Presumably not much. I say “post-nuclear” but it’s fair to call “Day at the Beach” a post-apocalyptic tale. And then Myra gets the idea to take her family to the beach. It’s a nice sunny Saturday—or at least she thinks it’s a Saturday; she’s unsure.

We aren’t told a lot about what life in such a future is like. We know oil is apparently a precious and fought-over commodity, like in Mad Max, and that the family is used to having to defend itself through violent means, as we’ll see later. What do they do for food? It’s not dwelled on. “Day at the Beach” is about ten pages long, and if anything it could be longer, which is the best kind of negative criticism. It’s a slice-of-life narrative in the allegorical mode, which as I said before reminds me of The Road, albeit with a lot less cannibalism. (There isn’t any on-screen cannibalism, don’t worry.) It’s a story about making way for the next generation, of “carrying the fire” as McCarthy liked to put it, in spite of horrendous circumstances. Myra and Ben are disfigured from the radiation and Littleboy is undoubtedly a mutant, but they don’t love him any less for it. Even Littleboy’s unconventional name alludes to the story’s allegorical nature, with the child being a stand-in for the next generation. As Anthony Boucher says in the introduction, it’s about “the endurance and adaptability of the human spirit.”

The family has a simple goal in mind, which is to hang out at the beach—alone. They don’t seem to have any mutuals, no oomfies or pookies to call on for such an occasion; but then maybe solitude in the midst of nature is what Myra and Ben want. It’s a tranquel scene, although I have to say I’m not sure if letting Littleboy go swimming in the buff was the norm for really young children in the ’50s or if it’s a casualness brought on by the end of civilization and public decency laws. Probably the latter. It does feed into the sense of tranquility, and of a kind of purity. They may not be a sight for sore eyes (although I must admit that going by her depiction in Ed’s cover, Myra rocks the bald look), but that doesn’t make them any less kind to each other. In the years during and following World War II there was much speculation on what life might be like in the wake of nuclear fallout, from Judith Merril’s “That Only a Mother” to Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz. The idea of humanity becoming mutated, with negative or possibly even positive effects, from the bombs was a popular one. Actually the “human mutants” stock is still high, if the continuing popularity of the Fallout series (now with its own TV show) is anything to go by.

Emshwiller seems to suggest that while life is rough, and some harsh decisions must be made, and although our descendants may look different from us, they (probably) won’t be any less human. Governments may fall and capitalism might (hopefully) end at some point (as Lovecraft says, “even death may die”), but the average person, with even a little bit of luck, will persist. Like the Okies in The Grapes of Wrath (indeed the migrant workers who now suffer on the receiving end of border violence), the survivors of nuclear catastrophe will not go quietly into the night. In a way it can be thought of as a response (although Emshwiller probably didn’t intend this, and anyway I have no way of proving it) to Merril’s most famous story—a ray of hope to the stark terror of “That Only a Mother.”

There Be Spoilers Here

I’m tired.

A Step Farther Out

So that’s it. End of the month. I didn’t end on the strongest note, but the Emshwiller is a good example of F&SF‘s range of fiction and willingness to take on more poetic material. In 1959 (incidentally this was the only story Emshwiller saw published in 1959) there were really only a couple options for “Day at the Beach.” Maybe Galaxy would’ve taken it. The genre SF market had shrunk massively; certainly it was no longer the market of near-endless possibilities that it would’ve been at the start of the decade. F&SF was arguably the only American SFF magazine that was doing really well at this point. The late ’50s and early ’60s were a low period for short fiction writers, and this was especially true the women. A lot of female writers would leave the field around 1960 in search of greener pastures, no doubt in part due to the market shrinking massively, and Emshwiller would be one of those women who stepped away from the scene.

But she would return.

See you next time.