Who Goes There?

Ursula K. Le Guin: you may have heard of her. She’s one of the most acclaimed authors in all of modern SFF, at times daring and yet somehow free of controversy (for the most part, as I’ll explain). She got started fairly late, only starting to write SFF when she was already in her thirties, but given that she lived to be almost ninety her career would be exceedingly long and varied. She’s also one of those rare authors to leave a major impact on both SF and fantasy, primarily with her Hainish and Earthsea cycles. The former might be her best work, when taken as a whole. My relationship with Le Guin has changed a good deal over time, ever since I first read The Left Hand of Darkness a little over ten years ago. As I’ve drifted closer to her politics over the past few years and become more familiar with her work I’ve come to have more mixed feelings on her as an artist, which I know is almost like a paradox. I think Le Guin is often great, and that of the Great™ SFF writers she’s one of the most versatile; but she’s also an idealist who doesn’t seem given to passions other than said idealism.

I’m gonna use her Four (later Five) Ways to Forgiveness as an example. Three of these stories were published in Asimov’s, with “A Woman’s Liberation” being the final one. It’s not a direct sequel to the previous stories, “Forgiveness Day” and “A Man of the People,” but it definitely complements those stories and more specifically could be seen as the yang to the latter’s yin. They share a few characters, but more importantly “A Woman’s Liberation” feels like a flipped-perspective retelling of “A Man of the People.” I’m not sure if this would work better as its own thing or if read immediately after the previous story like it would be in the collection. I enjoyed “A Woman’s Liberation,” but somehow feel it’s a weaker installment.

Placing Coordinates

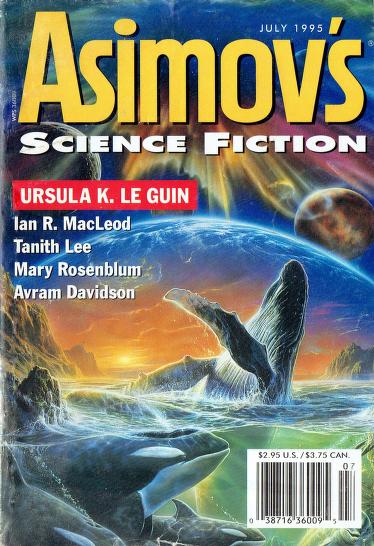

First published in the July 1995 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It then appeared in Four Ways to Forgiveness and by extension Hainish Novels and Stories, Volume Two. For anthologies we have The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Thirteenth Annual Collection (ed. Gardner Dozois) and A Woman’s Liberation: A Choice of Futures by and About Women (ed. Sheila Williams and Connie Willis).

Enhancing Image

The story is the fictionalized memoir of a former slave named Rakam, who having been freed years ago is now writing about her early years. We know at the start that things will turn out well for her in the end, which is good to know because to say Rakam had a rough childhood would be understating it. She was raised on Werel, as a slave, although her pitch-black skin suggests (indeed other characters take note of it) that she might be of noble heritage. Right, so on Yeowe and Werel dark skin is considered more desirable while light-skinned people are considered “dusty,” which seems to be an inversion of the dark-light dynamic among blacks that goes back to the days of chattel slavery. I suppose Le Guin is trying to make a statement about the arbitrary nature of skin complexion and desirability. Anyway, Yeowe has had a successful slave rebellion; its people are now free—or at least the men are. Slavery is still alive and well on Werel.

Rakam’s first sexual experience is as basically a sex toy for Lady Tazeu, the matriarch of Shomeke. Lady Tazeu is a curious character: she treats Rakam gently, all things considered, but is quite possibly a pedophile and also has a jealous streak. Lord Shomeke and Lady Tazeu also have a son, Erod, who is a young abolitionist and, as it turns out, Rakam’s half-brother. When she reaches a certain age Rakam’s mother tells her that there’s a reason for her dark skin: she is Lord Shomeke’s illegitimate daughter. But if Lady Tazeu ever finds out about this then she never tells Rakam. Lord Shamake falls fatally ill and the manor is placed under quarantine, and Lady Tazeu kills him and then herself; whether she does this so as to put the man out of his misery or out of revenge is left unclear. With both of his parents dead, Erod takes over the manor, and he signs papers that will free the slaves and allot them each a bit of money. This has disastrous consequences, as many of the slaves are killed overnight by neighboring slave-owners who think a rebellion is underway. Rakam is freed of her bondage, only to be forced into more servitude. Despite having her freedom papers, said papers mean basically nothing. “The government would not interfere between owners and those they claimed as their assets.”

You may notice that similarly to “A Man of the People,” this is less a proper novella and more like a compressed novel, giving us only the essentials for this narrative of one person’s life. We follow Rakam from her birth to not long before she would’ve started writing her memoir. One major difference between this and the other Yeowe-and-Werel stories (the ones I’ve read, anyway) is that “A Woman’s Liberation” is written in the first person. Despite this change in mode, Rakam’s style is actually not that different from the third-person narrators of the other stories, the only real difference being that those other narrators are omniscient, whereas there are little gaps in Rakam’s narrative—information she was never able to obtain. “I did not learn to read or write until I was a grown woman, which is all the excuse I will make for the faults of my narrative.” She still comes off as firmly literate, though, despite being a late bloomer when it came to reading. This is indicative of Le Guin’s long-winded style that she had developed by the ’90s, simultaneously craftine labyrinthine paragraphs that cram more information into overall less space. I’m not sure what inspired the change, but the Le Guin of the ’90s is quite different from how she was in the ’70s.

Le Guin’s style evolved, but so did her worldview it seems. The Dispossessed remains the quintessential left-libertarian SF novel, but I think it’s fair to say it’s not a feminist novel—or at least women’s liberation is not a chief concern. (The short story “The Day Before the Revolution,” a sort of distant prequel to The Dispossessed, could by contrast be considered an explicitly feminist narrative, although Le Guin doesn’t quite connect the dots with feminism and anarchism.) With the stories that make up Four Ways to Forgiveness Le Guin makes it pretty explicit that the notion of human liberty is incomplete without feminism—indeed freedom under a hypothetical socialism would be freedom only for a fraction of the population if women’s liberation is not a high priority. Erod starts out as a sympathetic character, albeit one who makes an error out of shortsightedness that gets a lot of people killed, but when we meet him again some years later he’s shown to be a low-key misogynist, much to Rakam’s displeasure. (Not sure where to put this, but isn’t it convenient that despite finding Erod attractive in her youth and even being offered to him as a bed-warmer, the half-siblings never get intimate?) Good news I suppose is that Rakam does meet a few decent men in her life, including Ahas, a fellow slave at the manor, and much later we meet a face or two that should strike us as familiar…

The thing about Le Guin that makes her a favorite of literary types and classroom discussion is that she’s such a pious writer—she’s so virtuous that she seemingly has never done anything wrong in her life. Her politics are very far on the left, which should on paper make her a no-no for those who try to keep literary discussion “apolitical,” but she’s so gentle about said politics. She might’ve become aware of this purer-than-pure status because—and I’m not sure when exactly this happened—she gets super-horny in the later Hainish stories. Oh sure, sexuality is integral to The Left Hand of Darkness, but in a clinical, anthropological sense. Women’s sexuality is also at the heart of “The Day Before the Revolution,” but we have not yet reached maximum levels of horny. Then we get to Rakam’s story, which at its core is about her political and sexual awakening, the two coinciding and indeed feeding off each other. Consider this passage, in which Rakam (and I have to think this is also Le Guin responding to critics) explains why much of her memoir is concerned with sex:

Now you may say in disgust that my story is all of such things, and there is far more to life, even a slave’s life, than sex. That is very true. I can say only that it may be in our sexuality that we are most easily enslaved, both men and women. It may be there, even as free men and women, that we find freedom hardest to keep. The politics of the flesh are the roots of power.

Rakam has been freed, but while she is technically a freed woman on Werel, she’s still a slave sexually; up to about the halfway point of the story the only sex she’s known has been through rape. Her orientation is a grey area: she’s probably bisexual, or even more likely pansexual since she doesn’t seem to think along gender lines when it comes to attraction. Le Guin is funny when it comes to sexuality because, given that she was most likely straight (I don’t recall reading about her ever being attracted to anyone who was not a man, and anyway she was very happily monogamous), her interest in queer yearning and relationships often has this sense of detachment—like she empathizes, but maybe she doesn’t know what it’s like to live as a man who sometimes has crushes on other men, who is always anxious about these crushes because coming out to another man could result in something far worse than a rejection. With the exception of the unrequited romance in The Left Hand of Darkness, I don’t usually buy Le Guin’s characters being attracted to each other—which brings me to spoilers.

There Be Spoilers Here

I said earlier that that a few characters from “A Man of the People” reappear here, although you don’t have to have read that story to understand what’s happening. The first is Old Music, the Hainish bureaucrat who has appeared in all the previous Yeowe-and-Werel stories in small but pivotal roles; and here he comes again, this time to help Rakam get off Werel, although she doesn’t discover until after the fact that he was Old Music. Once Rakam gets to Yeowe, which as I’d said is a liberated planet, we meet “Mr. Yehedarhed,” who you may recognize as Havzhiva, a Sub-Envoy for the Ekumen and the protagonist of “A Man of the People.” Finally there’s Dr. Yeon, a major character from that story and perhaps Havzhiva’s closest friend. Being an outsider, Rakam only knows so much about these people, but if you’ve read “A Man of the People” then you know a lot has happened. Rakam impresses Havzhiva and convinces him to let her found a publishing house, and in the process the two fall in love—the first time Rakam’s ever fallen in love with someone and had that affection returned.

The development of Rakam and Havzhiva’s happens over the course of maybe ten magazine pages, and if that sounds rushed, that’s because it is. It could be that, taken on its own, we simply don’t know enough about Havzhiva to trust him; oh sure, we’ve read “A Man of the People” and can carry that information over to this related story, but Rakam doesn’t know all that shit. The big things Rakam gets to know about her love interest is that he’s an abolitionist, a women’s lib sympathizer, and that he took a knife to the gut the fucking day he landed on Yeowe. From Rakam’s perspective, Havzhiva is basically perfect—which makes him boring. Because “perfect” people are boring. Le Guin admitted to dislike writing evil characters, which is why you can count the number of total scumbags in her fiction on one hand; but conversely she has a tendency at times to write characters who are seemingly bereft of human flaws. Goody-goodies, ya know. Rakam has trust issues and anxiety (understandably), but Hazhiva in the context of this story is a bit of a cypher, which hurts the romance.

A Step Farther Out

As I was reading “A Woman’s Liberation” I couldn’t help but feel like something was missing—indeed it’s the same reservation I have with the other entries in this “story suite” but even more so here. It’s good fiction but not good science fiction. Of the Yeowe-and-Werel stories I’ve read this one is the least SFnal, in that it could be most easily rewritten as a realistic narrative. Le Guin was clearly inspired by real-world slave narratives when writing it, but I think the lack of original input is to its detriment. I also think that while it does work well in concert with “A Man of the People,” it does feel redundant to some degree. Granted, I might be saying the same thing about that other story had the two been published in reverse order. Ultimately the problem could be that they’re too similar. I’m curious for when I eventually read Four/Five Ways to Forgiveness and see how these stories work together when taken as pieces of a larger narrative.

See you next time.