Who Goes There?

Frank Belknap Long had an exceedingly long life and career, born in 1901 and writing from about 1920 to well into the ’80s. He was close friends with H. P. Lovecraft, and was the first author to contribute to the Cthulhu Mythos, although it wasn’t called that in Lovecraft’s lifetime. “The Hounds of Tindalos” was Long’s third Mythos story, despite Wikipedia calling it the first to not be written by Lovecraft. This one story would have a rather large influence on Mythos fiction to come, with the hounds themselves even appearing later in Lovecraft’s “The Whisperer in Darkness,” in one of several instances of Lovecraft inspiring and in turn being inspired by others in the so-called Circle. There’s even an anthology of Mythos stories by different writers featuring the hounds. By the ’40s Long would move away from cosmic horror and focus more on science fiction, and indeed “The Hounds of Tindalos” is an early example of Long marrying the weird with the scientific, creating a structurally flawed but pretty memorable SF-horror narrative with an iconic monster at the center. It’s one of the more influential cosmic horror stories, and that’s because Long effectively utilizes one of the scariest things known to man: basic geometry.

Placing Coordinates

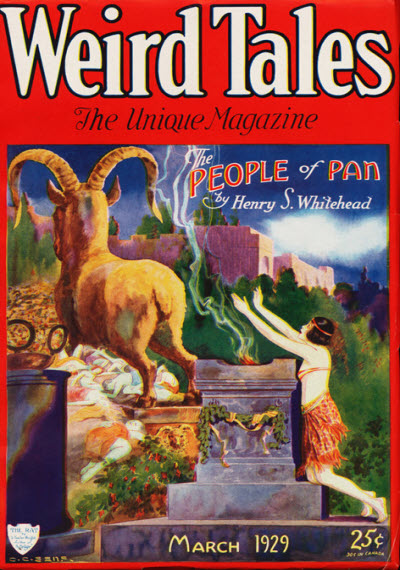

First published in the March 1929 issue of Weird Tales, which is on the Archive. It was then reprinted as a “classic” in the July 1937 issue, found here. It first appeared in book form in the Long collection of the same title, with a pretty gnarly Hannes Bok cover for the first edition. We also have Avon Fantasy Reader #16, found here. For anthology appearances there’s Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos: Volume 1 (ed. August Derleth), The Spawn of Cthulhu (ed. Lin Carter), and a real chonker of a book, The Science Fiction Century (ed. David G. Hartwell). “The Hounds of Tindalos” is a pretty famous Mythos story, so unsurprisingly it’s not hard to find.

Enhancing Image

Frank is an average guy who happens to be buddies with a real eccentric in the form of Chalmers, a sort of scientist-mystic who has contrarian views regarding objective reality. His library is filled with books on alchemy and theology, and “pamphlets about medieval sorcery and witchcraft and black magic, and all of the valiant glamorous things that the modern world has repudiated.” Or as Charles Fort would’ve put it, the excluded. Chalmers rejects what would’ve been conventional scientific narratives in 1928, although to Frank’s mild relief he does see Einstein as a kindred spirit, “a profound mystic and explorer of the great suspected.” Chalmers has a hypothesis that time, the fourth dimension, is actually an illusion, there merely because without it the human mind would wither at being able to see everything happening simultaneously. To test this he has concocted a drug which, if successful, should have the effect of breaking down that barrier. He wants Frank to be there as witness, and to act if something goes wrong. This is like your friend trying LSD for the first time and having you stay in the room with them for hours on end as a sober spectator, although LSD had not yet been invented when Long wrote this story.

Drugs play a surprisingly large role in the history of cosmic horror writing, although in the ’20s and ’30s these things were treated with utmost skepticism, if not contempt. In the context of a cosmic horror narrative the ambivalence makes sense. Sure, Aldous Huxley would later argue for the positive potential of hallucinogens, but for fiction with an overall thesis of “There are things man is better off not knowing,” it makes sense to go on an anti-drug screed. I’m not sure what experience Long would be basing his writing of this fictional drug on, although it seems he had been reading the Tao Te Ching and found it inspirational—but not for religious reasons. Chalmers takes the drug, which takes effect “with extraordinary rapidity,” and to say he has a trip would be understating it. What Chalmers expected happens, in that he not so much hops across bodies through time but experiences all these different perspectives at the same time; it’s that he can only convey this information to Frank in a linear fashion. But there’s something much more concerning that rears its head in the midst of this trip, which only Chalmers can see (not so much see as comprehend) and which forces Frank to break him out of the trance.

Let’s talk about the hounds, since they’re the star of the show, which is saying a lot since they never technically appear. We never see the hounds because they don’t exist in three-dimensional space. As Chalmers says, “There are […] things that I can not distinguish. They move slowly through angles. They have no bodies, and they move slowly through outrageous angles.” They’re only called hounds because Chalmers really isn’t sure what else he can call them; they’re certainly not like any dog in the real world, and they might only be distantly related to something mythical like Cerberus. In line with Lovecraft’s own conception of morality, the hounds are evil, but only as understood by humans. They act simply according to their nature, which apparently is an unspeakably horrific one. Or, as Chalmers says:

“They are beyond good and evil as we know it. They are that which in the beginning fell away from cleanliness. Through the deed they became bodies of death, receptacles of all foulness. But they are not evil in our sense because in the spheres through which they move there is no thought, no morals, no right or wrong as we understand it.”

Because Chalmers broke through the barrier of time he also stepped into the hounds’ domain, which if you know your cosmic horror is always a fatal mistake. The worst thing you can do in this kind of story is to alert the eldritch horror to your presence. So, there are basically two kind of geometry: curves and angles—cleanliness and foulness. Which sounds a bit silly as I’m saying it, but I respect Long for trying to apply a scientific rigor to something which refuses to be understood in human terms, even if math is supposedly the language of the natural world. This melding of the weird and scientific might’ve helped inspire Lovecraft in his own later, more SFnal Mythos stories, such as At the Mountains of Madness and “The Shadow Out of Time.” I can’t say for sure because I’m a layman and not a scholar. If you’re a Lovecraft scholar then feel free to call me a dumbass. Anyway, what makes the hounds memorable, despite never being seen in-story (though this hasn’t stopped people from trying, such as the aforementioned Bok illustration), is that they’re threatening while also not being god-like figures like Cthulhu or Shub-Niggurath; these are animals basically, as their name indicates, but they’re not puppers you’d wanna pet.

Unlike some other contemporary attempts at writing cosmic horror, Long’s language is fairly unadorned; even Chalmers, who is given to monologuing, is not as verbose as the average Lovecraft narrator. Frank (who might be a stand-in for Long) is less a typical cosmic horror narrator and more riding shotgun to the poor sap who normally would be narrating. Long might’ve done this one-degree-of-separation tactic because Chalmers is such an eccentric and so detached from normal human behavior that the reader (the God-fearing Christian reader who might dabble in the occult as a tourist) might not have anything to latch on to. This decision seems like a good idea, but as we’re about to see, it does have a serious drawback, which in my opinion stops “The Hounds of Tindalos” from entering masterpiece territory and instead relegates it to the realm of “pretty good.” I mean, there are far worse things you can be than pretty good.

There Be Spoilers Here

The story is split into five chapters, of which the first is by far the longest; this first chapter puts us in Frank’s shoes and the result is one long scene that happens in one location. So far so good. The second chapter, much shorter, sees Frank and Chalmers plastering up the angels in the latter’s room, since the hounds have been alerted and, as said before, enter through angles. But then Long makes the odd decision to jettison us from Frank’s flesh prison (Frank himself basically disappears from the narrative), and to switch perspectives to what seems to be a third-person view—and then to switch perspectives yet again. All in the span of just a few pages. Perspective, especially in a short story, is an important thing to keep consistent, and it’s a rule Long violates without (I would think) just cause. Of course things don’t turn out well for Chalmers; when do they ever. I think the last cosmic horror story I read where the protagonist/narrator comes out of the ordeal more or less intact was Robert E. Howard’s “The Black Stone” (review here); and yes I do consider Chalmers the real protagonist of Long’s story. On the plus side, Chalmers’s death manages to be both gory and genuinely creepy: authorities find his body with his head removed and placed on his chest, and yet there’s not a drop of blood at the scene. And to make things weirder there’s protoplasm on the body. Certainly no human could’ve done such a clean job, one that seems physically impossible—unless your existence is deemed physically impossible by known science.

A Step Farther Out

As I’ve been getting more into horror fiction I think I’ve come to appreciate the efforts of the “old masters” more. The irony with Long is that he would outlive Lovecraft and Howard by decades, but he never garnered even close to the amount of respect and impact as them—in death or in life. When he died he was so poor that he was initially buried in a potter’s grave, and it was only because of several big names in the weird fiction scene banding together that allowed him a proper burial about a year later. Clearly there’s some respect there, but if Long gets mentioned nowadays it’s very likely because he was buddies with Lovecraft. I know I haven’t helped with that problem. “The Hounds of Tindalos” points toward a talent who does indeed take after Lovecraft but whose priorities might lie elsewhere. If anything the quality of this story has made me curious in Long’s later, more mature work, albeit I know he drifts away from the cosmic.

See you next time.