Who Goes There?

Christopher Priest had a pretty long and dramatic career, and it pains me that (as far as I can remember) this is the first time I’ve read any of his fiction. I tried reading his novel Inverted World a couple months ago but had a false start with it; the timing wasn’t quite right. Inverted World is one of the cult classics of ’70s SF, even getting an NYRB paperback edition. (NYRB is like the Criterion Collection for book snobs, sorry but it’s true.) His novel The Prestige would be adapted for film by Christopher Nolan, which on the one hand must’ve brought some extra attention to Priest’s work but which he also didn’t seem to appreciate much—probably because Nolan told people to not read Priest’s book before watching his movie, which you have to admit is an asshole move. Speaking of assholes, I think the first time I heard of Priest was through the decades-long wait for Harlan Ellison’s The Last Dangerous Visions, the most famous SF book to never be published—until this year. I have thoughts on that. But Priest had spearheaded the controversy over Ellison seemingly refusing to finish his anthology with an essay called “The Last Deadloss Visions,” which got Priest a Hugo nomination. Incidentally, the final version of The Last Dangerous Visions had its publication announced shortly after Priest’s death. What timing, huh? I mean what are the odds J. Michael Straczynski would announce the upcoming release for TLDV one month after the death of its most ardent critic?

Anyway, “Palely Loitering” is my first Priest story, and while I’m ultimately mixed on it, I do have to admit it’s impressive. It’s a melancholy and mind-boggling time travel coming-of-age narrative that, given Locus classified it as a novella and the Hugos classified it as a novelette, seems to be one of those borderline cases in terms of length. I wish I had an ebook copy so I could run it through a word processor. I’m gonna be a bit liberal and side with Locus; it might come out to 18,000 or 18,500 words. People at the time were certainly impressed with “Palely Loitering,” as it won the British Science Fiction Award for Best Short Fiction.

Placing Coordinates

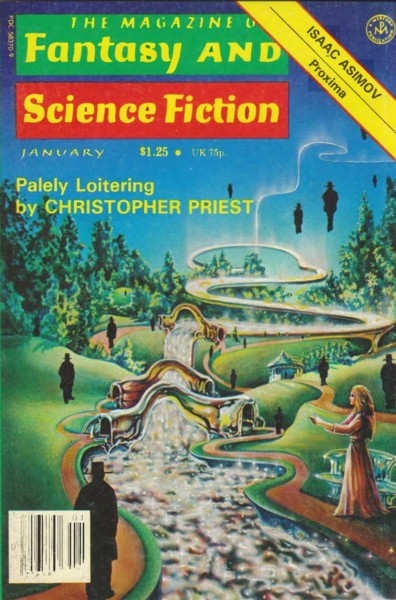

First published in the January 1979 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is on the Archive. It would reprinted in the Priest collection An Infinite Summer, named after the story Priest had given to Ellison for The Last Dangerous Visions and then retracted. It was anthologized in The Best Science Fiction Novellas of the Year #2 (ed. Terry Carr), The Mammoth Book of Time Travel SF (ed. Mike Ashley), and As Time Goes By (ed. Hank Davis).

Enhancing Image

Mykle starts out as a ten-year-old boy, moody even for his age, the sole son in a well-to-do British family who sometimes wants to get away from his sisters. It’s the future, in what is called the “Neuopean” Union (Priest never explains this), and the UK seems to be stuck, or at a crossroads between different eras. “We lived in the age of starflight, but by the time I was born mankind had long lost the desire to travel in space,” Mykle tells us. A big way to pass the time is to go to Flux Channel Park, a park in the Victorian British fashion that started out as a rather quirky invention. The Park was originally a “flux-field,” built for experimental space flight, which the government decided to have converted into a tourist attraction after the last ship to be launched from the flux-field did not return after several years. The Park is basically home to a time distortion field, with the Flux Channel having three bridges, each with different time properties. One bridge acts normally, while another would send you 24 hours into the past, and the third would send you 24 hours into the future. The flux-field, the “channel” itself, is not to be played with.

So of course Mykle jumps onto the flux-field.

The stunt lands him not 24 hours into the future but 32 years, wherein he meets an older (although not by that much) man who helps him get back to his own time. I’m not really spoiling anything by saying this older man is a future version of Mykle, which even Mykle admits is an obvious turn of events. “Although the answer seems obvious in retrospect it was some years before I realized it,” he says. The older Mykle is, as the younger one puts it, “pompous and over-bearing,” being preoccupied with a young woman he considers to be the most beautiful in the world—so beautiful that he dares not talk to her. Listen, I think a lot of us went through “simp” phases in our youths. At the same time young Mykle isn’t wrong when he thinks his older self is being self-serious, although the Mykle now narrating (whom we can infer is much older than either past self) is more sympathetic to the young man’s plight. Something to keep in mind when reading this story is that Mykle-as-narrator is telling us about events that would’ve happened many years in the past, and that he ends up referring to multiple past selves across different points.

“Palely Loitering” is interesting, historically, as a very telling work of ’70s British literature. Mind you that at this point, in the late ’70s, there was basically no market for short SFF to speak of in the UK; the major outlets like New Worlds and Science Fantasy had gone the way of the dodo, and while several notable SFF magazines would be born in the ’70s in the US, the same cannot be said for the UK scene. No doubt “Palely Loitering” would’ve been published in the UK first had there been a viable option, as it is quintessentially a British narrative, being obviously written in the wake of an economic recession, the waning of public interest in space flight (the last people would’ve walked on the moon about five years prior to Priest writing “Palely Loitering”), some of the worst flare-ups of violence in Ireland, and all setting the stage for the Thatcher administration which came about shortly after this story’s publication. There are scars in the British character still very much lingering from World War II three decades later. It’s little wonder then that those with enough money would try to jump into either the past or the future, and also that the fashion and manners of these people would be out of step with what we would expect from people of the future. Mykle’s own style of narrating is rather mannered, even for an Englishman—unless he were emulating the speech of an Englishman of the 1870s and not the 1970s.

I do have a few questions regarding the logistics of the flux-field and the Park, which Priest does not answer. Mykle breaks away from his family and jumps onto the flux-field itself pretty easily, apparently without any railing or fencing to stop people from landing on it. This seems like an obvious security oversight. If touching the flux-field directly lands you at some point in the distant future, then how would you hope to get back to your time? Mykle gets lucky with help from his future self, but most people wouldn’t be so lucky. How often would this sort of thing happen? For the sake of legal drama surely it must not be a common occurrence, and yet it’s hard to imagine people not constantly going off the beaten path out of curiosity and stepping on the flux-field often, damn the consequences. Wouldn’t it also be easy to run into past and future versions of yourself, given how the bridges work? Of course, this last point plays into the story: it does make sense, to a degree, for Mykle to meet past and future versions of himself, although then one wonders why we don’t see this happen with other people in the story. The Park seems like a Jurassic Park-level disaster waiting to happen, built with what Mark E. Smith would call “the highest British attention to the wrong detail.” But then maybe its dubiousness is also part of the point.

Of course, any story involving time travel will inevitably become a heady matter, what with how the rules of the story’s interpretation of time travel work. Sometimes meeting a different version of yourself would cause a time paradox and make the universe reset itself, or something like that, but time paradoxes are obviously common in the world of “Palely Loitering”—possibly even encouraged by the builders of the Flux Channel Park. Mykle’s chance meeting with the young-adult version of himself and seeing the woman (named Estyll) the latter is obsessed with plants a seed in his head, which will eventually make him map out the exact spot in the flux-field where he landed the first time so he can go back to that same point in the future. Despite seeing her again, however, as Mykle gets older he becomes more withdrawn, more introverted—in a way more pathetic. “As I grew older, and became more influenced by my favorite poets, it seemed not only more sad and splendid to glorify [Estyll] from a distance, but appropriate that my role in her life should be passive.” Slowly but surely he becomes the young man he had previously written off as a hopeless romantic. He is his father’s son.

Mykle’s sister drift in different directions as they get older, but more importantly there’s a tragedy in the family as the father dies before his time, and for better or worse Mykle’s father was an important man. Still only a teenager at first, Mykle matures and learns to run his dad’s business, eventually becoming one of the more important men in England—yet still he can’t bring himself to say another word to Estyll, seeing her as some kind of ideal even after he marries a different woman and by all accounts is happy with her. The obsessions never leaves his mind for long; it’s the kind of longing that probably doesn’t happen in real life and certainly doesn’t happen in the modern age, rather being the sort of longing Lord Byron and his ilk would’ve written about a whole century prior. It’s clear that Estyll does not fascinate Mykle strictly as a person, but rather symbolizes something which cannot be found in the present moment—only either in the past or the future, which the Park literally has bridges to. It’s tempting to think Proust helped inspire the story, especially Mykle’s ponderous and at times melodramatic narrative voice, but Priest is dead now and will not be answering anymore.

There Be Spoilers Here

Good news, the ship that mysterious vanished all those years ago is now returning! Bad news, it can only land on the flux-field and that means the Park will have to be dismantled! This happens when Mykle is now 42 years old, so 32 years after that fateful day when he jumped onto the flux-field and landed… 32 years into the future. Hmmm. The back end of this story is a bit convoluted, since it involves a middle-aged Mykle realizing that not only can multiple versions of himself exist in the same space but that these different versions don’t necessarily come from the same continuity. Yes, we’re getting into multiverse shenanigans with this one, although it wasn’t called that at the time and was pretty far off from becoming a worn-out concept. Looking at the cover for this issue of F&SF again, I realize it’s technically a spoiler, as the shadowy men in coats and hats are different versions of Mykle; but it’s out of context, so it’s fine. The ending, wherein Mykle basically plays matchmaker and gets an alternate past version of himself to finally go out with Estyll, is honestly moving, even despite the matchmaking antics being confusing to read in the moment. My heartstrings were pulled.

A Step Farther Out

Part of me wonders what this story would’ve read like had it been written by an American, but after a couple days of thinking on it that has more to do with my bias against Victorian-style narration than a fault with the story. It does get rather convoluted, but Priest got a lot done with this short novella, implying a whole future world whilst keeping the action more or less restricted to a single stage. It’s moody, just the right amount of bittersweet at the end, and perhaps most importantly for modern readers, it hasn’t aged much because of the deliberately anachronistic setting. After reading “Palely Loitering” I decided to read all of “The Last Deadloss Visions,” and these two tell me I might be a Priest fan in the making. I should get back to Inverted World, and maybe check out The Affirmation…

See you next time.

One response to “Novella Review: “Palely Loitering” by Christopher Priest”

As I mentioned earlier, I’m a huge fan of melancholic metaphorically-sculpted landscape style SF and fantasy. And of course, anything to do with the machinations of memory and ruminating on earlier versions of yourself. I described it in my shorter review as a story “dripping with the comfort and despair of memory.” This one resonated with me.

What Priest might you read next?

LikeLike